Commentary

Book Excerpt: Shoring Up Display's Weak Spots

- by Linda Abraham , July 18, 2012

An in-depth look from comScore at the five areas marketers need to focus on to make sure they get what they pay for

An in-depth look from comScore at the five areas marketers need to focus on to make sure they get what they pay for

Back in January, comScore released a new way to account for the impressions made by digital display advertising, following many of the guidelines laid out in the industry’s Making Measurement Make Sense (3MS) initiative.

We call this solution the Validated Campaign Essentials (vce), and it provides an unduplicated accounting of impressions delivered across a variety of dimensions, helping to

significantly improve the value of online advertising. (Importantly, VCE gleans all this information via a single ad tag, thus enabling a comprehensive, but holistic, view of digital ad delivery. The

use of a single ad tag is a critical component of this measurement approach, as it evaluates all impressions consistently and eliminates all issues associated with duplicated measurement.)

To

test-drive vce and to better understand issues associated with display ad delivery and validation, we included 12 major marketers, among them Kraft, Sprint, Kellogg’s, Ford and Kimberly Clark,

in the U.S.-based VCE Charter Study. (Results are presented in aggregate form, to protect their confidentiality.)

The goal was to find out what’s not working, and to quantify the

incidence of sub-optimal ad delivery. And what we found was that when it comes to digital display, marketers are not necessarily getting what they expect when they buy online ads. From ads delivered

next to objectionable content to ads that never had the opportunity to be seen, there are countless examples where the digital medium is simply not delivering on its promise.

The study

found five areas marketers should pay closer attention to.

1. In-View Rates Are Eye-Opening

The study showed that 31 percent of ads were not in-view, meaning they never had an

opportunity to be seen. There was also great variation across sites where the campaigns ran, with in-view rates ranging from 7 percent to 100 percent on a given site. This variance illustrates that

even for major advertisers making premium buys, there is a lot of room for improvement.

One of the most fundamental aspects of advertising measurement, particularly as it relates to

cross-media, is the need for a solid and consistent method of determining whether a consumer had an opportunity to see (ots) an ad. In television, once an ad is delivered in a program, it plays,

meaning that the consumer had an opportunity to see it. While the person might not have been in the room to see the ad, the industry accepts the notion that the opportunity was still there and

therefore it gets counted as such. Alternatively, if the television is turned off, there isn’t an opportunity for it to be seen.

The advertising industry has accepted ots as a

standard metric, which many rely on to build cross-media campaigns and to assess the effects of advertising across channels. This metric is particularly important based on the very simple fact

that:

• If an ad does not have an opportunity to be seen by a real user, then it cannot possibly deliver its intended effect.

• When compared to other forms of media,

digital advertising has unique characteristics relating to an ad’s opportunity to be seen. To date, the standard has simply been to measure whether ads were served to a page. However, there are

many reasons why a served digital ad might not result in someone having an opportunity to see it. For example, consumers often land on a particular page and then quickly scroll down to consume content

before the banner ad at the top of the page has had a chance to load. An alternative scenario is when a user remains at the top of the page, never scrolling to the bottom where many ads have loaded.

Given these scenarios, which inherently result in many ad impressions being delivered but not seen, the industry has begun to evaluate ways to accurately measure viewability and to improve in-view

rates to avoid wasted ad spend. 3ms proposed a standard definition of in-view, which states that at least 50 percent of the pixels of the ads must be in-view for a minimum of one second.

2.

Targeting Audiences Beyond Demos Can Be Powerful

Generally, campaigns that had very basic demo-targeting objectives performed well with regard to hitting those targets. For example, those

with an objective of reaching people in a particular broad age range did so with 70 percent of their impressions. Predictably, as additional demographic variables were added to the targeting criteria

(e.g., income + gender), accuracy rates of the ad delivery declined. However, the results also showed that, on average, 36 percent of all impressions in a campaign were delivered to audiences with

behavioral profiles that were relevant to the brand (i.e., consumers with demonstrated interests in categories, such as food, auto or sports). One campaign had 67 percent of its impressions viewed by

the target behavioral segment, demonstrating that targeting to people based on interests or behaviors holds strong potential.

3. The Content in Which an Ad Runs Can Make or Break a Brand

Of the campaigns analyzed, 72 percent had at least some impressions that were delivered adjacent to objectionable content. While this did not translate to a large number of impressions on

an absolute basis (141,000 impressions across 980 domains), it is important to note that 92,000 people were exposed to these impressions. This demonstrates that even with the most premium of

executions, brand safety should be of utmost concern for advertisers.

Defining brand safety A major concern of all marketers is the relevance of the content in which their ads are

delivered. When brands spend money on advertising, they need assurance that their ads will not run next to content that is at odds with the brand they are trying to build or the equity they have

already established.

In this context, “objectionable content” can generally be categorized into two buckets, the first being rather objective and the second being much more

subjective and brand-specific:

Type I: Adult-Content and/or Hate Sites

Almost all brands want to avoid having their ads run on Adult-Content or Hate sites. Although there might

be some differences of opinion on exactly what sites fall into these categories, there are generally agreed-upon and industry-endorsed lists that define these, and almost without exception, reputable

marketers want to avoid them at all costs.

Type II: Brand-Specific Criteria

There are topics, issues and/or content that certain brands don’t want to advertise near because

it directly conflicts with and/or detracts from the advertising’s objective. For example, consider a major airline. For obvious reasons, an advertiser in this space might not want the

brand’s ad to appear next to an article about significant plane delays. Meanwhile, for countless other advertisers, delivering an ad to a consumer in this content would be completely benign.

Brand Safety on Adult-Content and Hate Sites

To begin to understand the extent to which ads are delivered in content deemed inappropriate, the vce Charter Study quantified the

incidence of ad delivery on Adult-Content and/or Hate sites (Type I). The study used a standard definition of “objectionable content,” based on historical data of sites/categories most

commonly identified as being “not brand safe” by leading advertisers (See Figure 16).

To the surprise of many advertisers in the vce Charter Study, 72 percent of the campaigns

had at least some impressions served in this type of inappropriate content, which spanned a total of 980 sites (See Figure 17). The good news is that the actual percentage of impressions involved was

quite small, less than .01 percent. However, the study also showed that 92,000 people saw these ads, meaning that if some of these people were either loyal or prospective customers, it could be

counterproductive and/or problematic for the brand.

It should be noted that it is likely that this number is much higher when evaluating the broader, online advertising universe as there

are certain factors that may have positively influenced the low percentage of inappropriate ad placements in the vce Charter Study. These factors include:

• The brands under

measurement were premium national marketers and therefore more likely to use higher quality content.

• Many of the brands were already employing ad-blocking technologies from external

third parties. Even with these technologies in place, several instances of inappropriate placements still appeared.

• In a few instances, select demand-side platforms chose to

obfuscate the urls where the ads were run, meaning that brand safety could not be measured and clients could not validate where the ads were run.

Despite the relatively low overall

incidence of ads appearing next to inappropriate content, these findings still might be unsettling to advertisers. Even one ad impression delivered in the wrong environment can damage a valuable

consumer’s feelings toward a brand. With the increasing use of social media, a snapshot of a marketer’s ad in an inappropriate environment can quickly go viral, exposing many more people

to the unintended, but negative, association of a brand and inappropriate content. With 92,000 people being exposed across all vce Charter Study campaigns, the advertisers’ concerns are

justified.

4. Fraud Is the Elephant in the Digital Room

Fraud is an undeniably large and growing problem in digital advertising. The results showed that an average of 0.16

percent of impressions across all campaigns was delivered to non-human agents from the iab spiders and bots list. Although this percentage might appear negligible, there are two important

considerations to keep in mind. Only the most basic forms of inappropriate delivery were addressed in this study. When additional, more sophisticated types of fraud are considered, the problem will

only get larger. Like brand safety, fraud should be an important concern for all advertisers.

Defining fraud Today’s world of online advertising involves many players in the

ecosystem, each with a specific role and goal. However, the inherent complexity in this landscape results in a lack of control and visibility into online ad delivery. While the vast majority of

individuals in the digital advertising ecosystem operate with the best of intentions, like any industry, there are fraudulent players that can disrupt the value chain. The complicated daisy chain of

ad delivery can involve up to 20 different players, and quite often neither the buyer nor the seller has insight into each step in the process.

The term “fraud” as it relates to

online advertising encompasses a variety of impression-delivery scenarios. In some cases, there is direct fraud, which is deliberate and completely illegitimate, while other types of fraud are an

unintentional by-product of legitimate business practices. In either case, this fraudulent activity does not deliver ads to actual people as intended, so should therefore be excluded from validated

impression counts.

To help members of the online advertising ecosystem better understand and avoid issues relating to fraud, the iab maintains a list of all known non-human spiders and

bots. All iab-accredited ad servers are required to filter out these known sources of non-human ad impressions. The use of some of the spiders and bots on this list is a completely legitimate practice

employed by many Web sites for a variety of uses, such as to gather data to help index pages for search engines or to determine page content for the purposes of offering contextual ad placements.

Regardless of their use, however, they do not deliver ads to consumers and can therefore wreak havoc on ad delivery and validation, causing a lot of wasted ad impressions and skewing the results of

advertising-effectiveness measurement. An analysis of vce Charter Study campaigns showed that the average campaign in the study had 0.16 percent of total impressions being delivered via these spiders

and bots.

In addition to known spiders and bots, part of the vce Charter Study analysis included an evaluation of fraudulent impressions that were intentionally delivered via illegitimate

online activity. Campaign delivery was manually reviewed for unusual activity indicative of intentional fraud. Such indicators might be unusually high or unusually low in-view rates or little or

excessive mouse movement on the creative. Upon identifying these outliers, further human investigation was used to either confirm or negate the hypothesis.

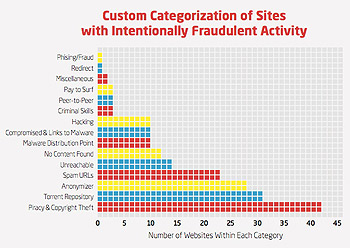

The analysis revealed more than

200 sites that were guilty of this type of fraudulent delivery. Figure 19 below outlines some of the most common categories of sites with such activity. Additionally, the investigation uncovered that

one of the sites delivered almost 2 million ads in the vce Charter Study, supporting the need for consistent hygiene on campaigns to accurately measure delivery and ensure only ads that are delivered

to actual humans are counted in validation and effectiveness measurement. Again these ads were not blocked from serving for the purposes of this study, but instances of delivery were measured.

While these two categories of fraudulent ad delivery accounted for only a small percentage of total ad impressions in the vce Charter Study, there are a variety of other sources of fraud that

consistently result in significant waste. For perspective, of the approximately 1 trillion urls that comScore processes each month (40 percent more than all the traffic of the entire u.s. Internet

population), the application of comScore’s full suite of fraud detection technologies identified levels of fraud ranging from 3 percent to 10 percent for a given campaign. Clearly, no brand is

immune from fraud, and it should be an area of concern for all players in the ecosystem.

5. Digital Ad Economics: The Good Guys Aren’t Necessarily Winning

The study showed

that there was little to no correlation between cpm and value being delivered to the advertiser. For example, ad placements with strong in-view rates are not getting higher cpms than placements with

low in-view rates. Similarly, ads that are doing well at delivering to a primary demographic target are not receiving more value than those that are not. In other words, neither ad visibility nor the

demographic target delivery is currently reflected in the economics of digital advertising.

Putting all of the Pieces Together

The vce Charter Study demonstrates that each

dimension of ad delivery — viewability, audience targeting, geographic targeting, brand safety and fraud — has a significant impact on whether or not an ad has an opportunity to achieve

its intended objective, and should therefore be a central component of ad delivery validation measurement.

Advertisers want to understand ad delivery to each of these core dimensions, and

they also require a holistic, unduplicated view of total campaign delivery. In order to achieve this unduplicated accounting of delivered impressions, advertisers require a simple solution that

eliminates all of the wasted time and error associated with merging disparate data sources.

Consider, for example, results from a single campaign in the vce Charter Study:

• 38.9 percent of the ads were delivered to the right target audience;

• 58.0 percent of the ads were delivered in-view;

• 85.7 percent of the ads were

delivered in the right geography.

But note that the study goes on to say that in this sample campaign, just 33 percent of the ads were delivered according to plan.

Across all

dimensions of ad delivery, the VCE Charter Study demonstrated clear examples of situations where ad impressions were largely wasted.

And since study participants included major branded

advertisers, who inherently buy more premium inventory than the average online marketer, the study findings are not necessarily representative of the overall online advertising market. In fact,

because these advertisers generally engage in high-end, premium campaigns, the findings may represent “best-case scenarios,” rather than the norm.

That shows us that regardless

of the quality of the buy, there is almost always room for improvement. Advertisers who understand and leverage the power of validation stand to gain much more value from the digital channel.