Commentary

The Medium Is The Line Item

- by Joe Mandese @mp_joemandese, June 13, 2022

McLuhan was wrong. The medium isn’t the message. Apparently, it’s the line item. Or at least, it’s in the eye of the individual or entity beholding it. That’s one of the takeaways I had from GroupM’s briefing late last week about the mid-year forecast it released this morning, and particular, a “sidebar” that Global President of Business Intelligence Brian Wieser called out with some importance: that the increasingly fungible nature of how someone defines a medium, will increasingly make it difficult, if not impossible, to bucket that medium as an explicit ad medium.

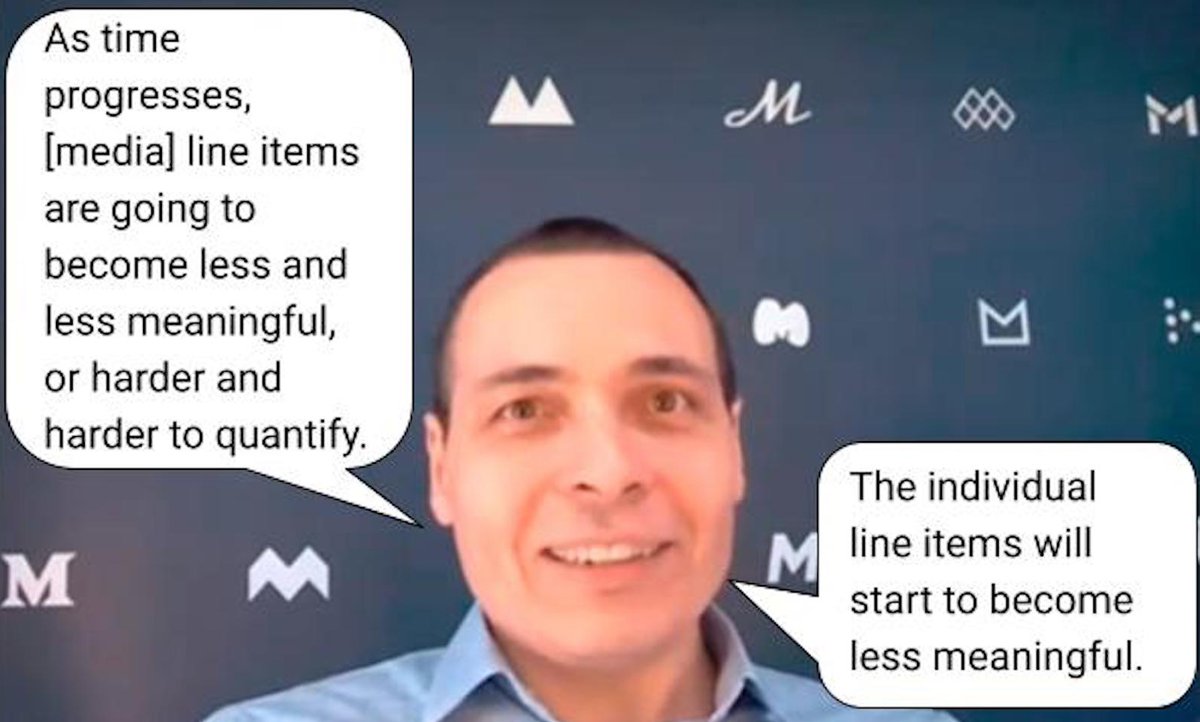

“One of the things we thought was really important to call out was the blurriness of media and how everything is evolving in a way that makes the individual line items increasingly less relevant,” Wieser said during a pre-release briefing with reporters, adding, “Thirty years ago, if you were to look at a data set like this, print was print, radio was radio, TV was TV. No real ambiguity about what’s what. And with every passing year, this is getting increasingly challenging.”

Wieser then posed a question: “How exactly should one categorize The New York Times? Is it print? Is it digital? Is it audio? What do you do with YouTube? Is it television? Is it search, because by the way, it might be the second biggest search engine? Is it social media, well, because it’s actually kind of a large social network too.”

Obviously, this creates some challenges for a guy like Wieser who has spent his career categorizing things in order to accurately calculate – and forecast – ad spending, and it was far from the first time he did some soul-searching on the subject.

It’s been 13 years since I tailed Wieser around New York City, live-blogging his “Social Sojourn” in real-time via my Blackberry (a line item that no longer even exists) so he could benchmark whether “social media” was in fact an advertising medium – and a line item that should go into his U.S. and worldwide ad spending calculations.

Interesting, Wieser then the head of Interpublic’s forecasting unit, concluded social media was “not” an ad medium and therefore should not be factored into his advertising models.

True to his word, 13 years later Wieser still does not have a line item for “social media” in GroupM’s ad calculations and forecasts, and during the briefing, he said it was for the same reasons he cited 13 years ago. That while big social media platforms such as Facebook, TikTok, etc. do sell billions of dollars worth of “advertising inventory,” it for the most part is not in the spirit of any genuine “social strategy.”

The good news for Wieser and his GroupM colleagues and clients, is that his calculations are not dependent on the definition of any given media “line item,” “bucket,” or whatever you want to call it. That’s because years ago he switched from the ad industry’s traditional top down approach to ad forecast modeling – developed originally by Madison Avenue’s pioneering forecaster, McCann-Erickson’s Bob Coen – and shifted to a bottom’s up approach that effectively calculates aggregate ad spending by adding up the advertising revenues reported by media companies.

It’s a little more sophisticated than just that, but the shift was either prescient, or a lucky one for Wieser, because it makes his aggregate forecasting bullet-proof, even as the ability to define what bucket each line item belongs in.

Ultimately, Wieser said advertisers and their agency account groups, increasingly define those line items based on how they view the role of a medium in the way they influence consumers, not how economists do.

So I asked Wieser to address how that is evolving for so-called Web3 platforms such as NFTs, DAOs and the metaverse, etc.

Not surprisingly, he it’s still early days for a succinct industry-wide bucketing of any of it, and defaulted to the individual advertiser perspective, offering the virtual global gaming platform Roblox as an example, because it is one of the platforms many cite as an early example of the metaverse.

“Take Roblox,” he said. “If you decide that the metaverse is a thing. And you decide that it’s going to be a bigger thing and you want to understand how this thing you’re calling ‘metaverse’ impacts consumers, and you’ve created that line item for yourself as an individual marketer, well, you’re going to bucket a bunch of other things together to create a certain amount of scale to be able to study and understand it. And to think about how you should optimize your plans.

“But a different marketer might say, ‘Well, there’s no thing that we’re calling metaverse. There’s no thing to bucket. We’re going to keep Roblox as digital,’ let’s say. And now we’re going to compare it against other digital properties and we look at the effectiveness of digital, and we’re trying to forecast the effectiveness of digital and Roblox is just part of that. And whatever the metaverse becomes, is just part of that bucket.”

Lastly, I asked Wieser whether the way individual advertisers ultimately bucket new media matters and how much of a difference it could make in the long run.

“I do think it matters how media gets bucketed and what the taxonomies are that individual marketers have, but the problem is that those taxonomies are going to vary so widely from marketer to marketer, that it starts to lose meaning over time,” he explained.

So maybe the real answer isn’t that the medium is the line item. Maybe it’s that the medium is actually in the eye of the beholder.