Commentary

Selling Stories Tomorrow, Now

- by Douglas Quenqua , October 13, 2011

Innovative digital shops are transforming the way stories are told

The fundamentals of storytelling are timeless. Good characters will always need obstacles to overcome, the best villains will always have their soft side (“Luke, I’m your dad”) and whenever possible, a life should hang in the balance.

But new media provide new ways of telling stories. Radio made them mass market; television turned them visual; the Internet can render them interactive. Today, as new media platforms seem to emerge with the frequency of superhero films, the opportunities for storytellers are greater than ever before.

Capitalizing on those opportunities are a handful of companies that operate in the ever-narrowing valley between Hollywood and Madison Avenue. These companies use mobile devices, email, GPS, even old-timey fax machines (wait for it) to create entire worlds into which their audiences can get lost. At the heart of their work are simple stories told well, only with bells and whistles the likes of which Ovid never imagined.

Whether for marketers or movie studios, what these agencies are doing represents the future of storytelling: interactive, nonlinear, three-dimensional and constantly evolving. Their work is by nature experimental, and not something most clients or audiences are likely to embrace quite yet. But a look at what they’re doing today could give us all an idea how good stories might be told tomorrow.

Campfire

Get a group of advertising executives talking about multiplatform storytelling, and the conversation will inevitably wend its way around to Audi’s Art of the Heist, the 2005 campaign that fired the starting gun for marketers staging alternate reality games (ARGs). One of the cocreators of that campaign (along with more traditional advertising agency McKinney) was Campfire, an ad agency cum production house founded by three independent film producers — two of whom helped create the 1999 movie The Blair Witch Project. So invested in the art of storytelling is Campfire that its founders chose a name that evokes the simplest, most elemental form of it.

The Art of the Heist was a real-life adventure in which 500,000 consumers assisted in a 90-day international manhunt for the thieves who boosted an Audi A3 from a Manhattan showroom. Billboards, print ads and TV commercials asked the public for help recovering the vehicle; Audi’s Web site sent them to a site for a fictional investigation firm run by a sexy woman and her geeky partner, which lead them to a suspicious character attending that year’s E3 show, and on and on down the rabbit hole. Not only did the effort win a slew of Cannes Lions, Clios and MIXX awards, it spawned a million imitations from creative directors suddenly obsessed with audience engagement on a mass scale. Since then, Campfire has done multiplatform immersive campaigns (ARGs and otherwise) for HBO, Verizon and the Discovery Channel.

Cofounder Mike Monello says that telling a story through interactive media — one that people might want to get involved with for weeks at a time — means supplementing a storyteller’s sense of drama with a puppetmaster’s cunning.

“When you’re thinking about telling a story across multiple channels, you’re thinking a little less like a storyteller and a little more like an architect, in that you’re going to architect an experience using all these tools and it’s not really complete until all these people are in it,” he says.

Campfire’s particular contribution to the craft of storytelling is the art of using one media to send audiences to another, all the time moving the story forward, so that the audience “feels like they’ve experienced the story as opposed to [feeling like] they’re being told the story,” Monello says.

Take, for example, the agency’s 2008 campaign for HBO’s True Blood, the now-hit gothic series about vampires in the Deep South. The cable network asked Campfire to build anticipation for the show among audiences with a predisposition toward vampire stories: Fangoria subscribers, horror-movie bloggers, members of “goth” message boards, etc. But rather than create a Web series or something similarly passive, Campfire created a mystery for them to follow that jumped from snail mail to social media to Web videos to print ads and back again.

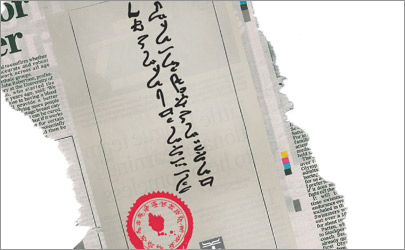

Five months before the show premiered, Campfire mailed letters enclosed in black envelopes sealed with wax to members of the target audience. The letters themselves were written in dead languages such as Babylonian and Ugaritic. Because most of the recipients had no idea what the letters said, they — predictably — went online to their blogs or message boards seeking translations (the agency also set up fake blogs to help move the story along). Once deciphered, the messages led the players to a Web site, guarded by a beautiful female vampire, where they could watch short videos fleshing out the series’ backstory. Next came the nationwide print ads for Tru Blood, a fictional beverage from the show. While most of the country tried to figure out what it was all about, the original participants were receiving vials of actual Tru Blood in the mail.

Key to the success of such “transmedia” campaigns — a catchall phrase increasingly used to refer to stories that leap from one media platform to another — is taking advantage of the unique properties of each platform, says Monello.

“It’s not just like, oh, I’m going take a story and break it down and put it on a bunch of different media platforms and force people to hunt it down,” he says. “It’s how can I take a movie and a comic book and a video game and create a scenario where each one of those elements brings to life some aspect of the story using unique properties of that media channel.”

The result is an experience that goes deeper than watching a movie, he notes, because the “viewer” becomes intensely invested. It also creates a three-dimensional world that can flesh out a simple story in a dozen different ways.

Luckily for agencies like Campfire, more and more clients are starting to see the wisdom of operating that way, Monello says, if only because increasingly savvy audiences are coming to expect it.

“What we’re finding is more and more people are looking at how Alan Ball works and how people like J.J. Abrams and Josh Whedon work and realizing they need to start [to] think about their story — whether it’s a TV show or a movie — they need to start thinking about them as larger than that singular experience,” Monello says.

He is hesitant to discuss how he sees his kind of storytelling evolving in the next 10 years —“I try not to

concern myself with what I can’t do now,” he says — but he admits to being excited about the increasing personalization of media, which could give storytellers like him “the

ability to create experiences that are tailored to people.”

“Whether it’s the quality of mobile devices — we all have little computers in our pockets now — or the

sophistication of the browsers and the programming languages like HTML5,” he says, new technologies “will allow us to do so much more than we can do now.”

Just as they could have done had the technology been around in 2005. Asked if he could imagine doing Art of the Heist now, when most people walk around with GPS-capable phones, he sighs, “Oh, that would be so much different if it were done today.”

Blacklight Transmedia

Of course, not all transmedia stories are ARGs. As any sci-fi fan can tell you, classic franchises like

Star Trek, Dune, Batman and even Star Wars have long played out semi-simultaneously through movies, comic books, novels, video games and TV series, with story lines that complement each other more

often than they conflict.

But in the age of digital media, companies like Blacklight Transmedia are working to make multiplatform storytelling more seamless, complementary and, hopefully, more

entertaining, than ever.

Zak Kadison spent his entire career as a TV and film executive — most recently at now-defunct Fox Atomic — before cofounding Blacklight two years ago to offer a new way to approach transmedia content.

His problem with Hollywood’s approach to multiplatform storytelling was its tendency to focus solely on the movie version of the story to the detriment of other media. “The studio starts to think about getting a video game made 18 months before the movie comes out,” he says, “but it takes three or four years to make a good video game. It takes two years to write a good book. But the guy in the licensing department doesn’t care about that. He just wants to license the content to whoever will pay the highest amount, which almost ensures an inferior product.”

Studios also tend to use alternate platforms only to retell the story of the movie — hence the perfectly superfluous “novelization” of movies like, say, Caddyshack — rather than tell stories that will complement that narrative and therefore grow the entire fictional world.

(Equally vexing to Steve Peters, founding partner of NoMimes, was the studio system’s increasingly desperate habit of recycling old stories. “Asteroids,” he says, referring to the classic arcade game. “No characters, no backstory to build on. But Hollywood bought the rights for a lot of money. I didn’t get in to this business to do Tic Tac Toe : The Movie.”)

The

mission of Blacklight is to create intellectual property that can be produced simultaneously on multiple platforms, hence creating true transmedia experiences.

For each project, Backlight

creates a master book of narratives — what Kadison calls “The Bible”— that outlines every story for every platform, from film to books to Web series, even to Facebook games.

They then sell the rights for each specific medium to different entertainment companies, with whom they partner to create the actual content.

So far, Hollywood seems to approve. In just two years, Blacklight has sold four concepts. Earlier this year, Walt Disney Pictures acquired the film, interactive and publishing rights to Runner, a dystopian time travel adventure, with Brian Grazer attached as a co-producer. Warner Brothers bought the film and digital rights to a project called Blood Wars, and Universal acquired the TV and movie rights to something called Arabian Knights.

Of course, working this way requires a thoroughly modern approach to storytelling. “All the story lines are self-contained,” Kadison says, meaning a viewer can discover any story in any order and still enjoy it. They also must each contain enough plot twists and surprises to keep audiences interested without spoiling any of the other plot lines. It’s an unusual challenge for a storyteller, but one that Kadison says anyone working in entertainment needs to be ready to embrace.

It also just happens to be extremely marketer-friendly. “We build brand integration into all our bibles,” he adds.

Whether it’s a process that will work as well for romantic comedies as it might for sci-fi and fantasy properties remains to be seen. Do fans of Katherine Heigl’s character from 27 Dresses really want to read the graphic novel delving into her backstory?

Maybe, says Peters.

“On Dawson’s Creek, Dawson kept a journal about his innermost feelings, but they never told you” what those feelings were on the show, he says. “However, if you go to Dawson’s Web site, you could read those stories.” Peters also points out that when Miley Cyrus used to go on tour between seasons of Hannah Montana, she did so as Hannah Montana, not Miley Cyrus. The fact is, transmedia storytelling is already accepted by mainstream audiences more than most people might realize.

NoMimes

For evidence that the mainstream is taking an interest in 360-degree storytelling —particularly clients — take a look at the short history of NoMimes, a transmedia agency based in Los Angeles. Formed in 2008 by three former employees of 42 West, an agency renowned for some memorable ARG work (most notably the campaign launching The Dark Knight), NoMimes has so far made its mark staging elaborate ARGs for large corporations — not for their customers, but for their employees.

“Interestingly, we’ve been commissioned by corporations to do ARGs as team-building exercises,” says founding partner Peters. “We’ve done three for Cisco in the last three years.”

Each of those ARGs centered on a mystery, such as a case of corporate espionage or a stolen journal that contains clues to an international conspiracy, which Cisco employees had to solve as a team. Typically, the fictional characters use Twitter and Facebook to keep in touch with the players and drop clues — as simple as email addresses or as technical as GPS location data — that would lead them to the next step of the game.

“The basic mechanics of an ARG is a sort of Internet archeology in that you’re not so much told the story as you find evidence that the story leaves behind,” Peters says. “You may stumble across the security log of a lab that shows everyone who’s gone in and out of the lab in the past two weeks, and using this log you can infer quite a bit of information, as opposed to someone just blogging about it and giving narrative about what happened.”

The development of sophisticated mobile technology has also allowed NoMimes to incorporate more real-life elements into its narratives. “We hid a piece of information in a park in Oslo, Norway,” recalls Peters, “and not only did [the players] have to figure out the location, they had to use their own social networks and engineering to find someone that may or may not have even been playing the game to get them the information and move the story forward.”

Naturally, the outcome of the games always hinges on the use of Cisco technology. But Peters stresses that conceiving a good transmedia campaign means that technology, even in stories created for employees of a major tech firm, should always be used in service of the story — never the other way around.

“First and foremost, the story comes first and the transmedia pieces need to serve the story,” he says. “We’ll write the story first, and come up with story arcs and story points, and then develop it from there.”

And don’t get hung up on always using the newest technologies, either. “We did a thing for a World War II story where we found a lesser-known technology, this thing called a Herkimer radio transmission that transmitted photos over the radio — like a fax machine with no wires,” says Peters. “That was kind of retro tech,” and it added a layer of authenticity to the game.

One challenge facing all creators of interactive, multiplatform stories is creating clues that are tough enough to be interesting, but not so tough that the players give up. If a clue is harder than the story is compelling, your players are likely to just wander off, like bored moviegoers walking out of a theater.

This is what happened to me when I visited NoMimes’ Web site, where visitors are invited to participate in a short ARG. Enter your email address and watch your inbox, the site says. “The experience will begin immediately and last 10-15 minutes.”

Sure enough, I quickly received an email from someone claiming to be the headmistress at the International Mime Academy, complete with a link to a Web site for the fictional institution. The only actionable information I found on that site was a phone number with a Los Angeles area code, but because it was 5 a.m. on the West Coast at the time — and because there was not yet any real story to speak of — I wasn’t particularly compelled to dial the number, and forgot all about the game until Peters reminded me of it.

“That’s the biggest challenge for transmedia content right now,” says Peters. “Every time you ask an audience member to take a step, even if it’s just clicking through a link, you run the risk of losing them.”

“The most books ask you to do — as far as interactivity goes — is turn a page,” he says. “I want to find the transmedia equivalent of a page turn.”

Surprised there's no mention of Fourth Wall Studios, founded by the earliest players - Elan Lee, Sean Stewart and Jim Stewartson – in the ARG and transmedia space, who created I Love Bees and The Beast, among others. Nice article, still.