Commentary

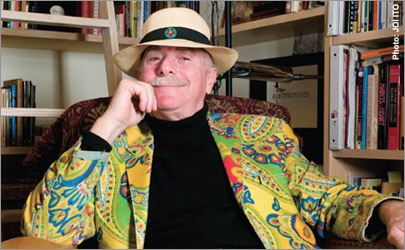

The Future of, Well, Us: A Conversation with Howard Rheingold

- by editor , October 13, 2011

How are we evolving because of the changes in media?

I think you can make a very strong case that the technologies we have created — and the media that we make out of some of those technologies — is, in fact, how humans have evolved. This is, of course, in the realm of theory, but it is not “blue sky” theory.

If you look at the earliest artifacts of human communication — like cave paintings, done 35,000 to 45,000 years ago — humans begin to learn by imitation, and it takes on a kind of Darwinian process, because we were able to make models of what others were doing. You can watch somebody chip an axe blade and the same parts of our brain will light up as would if we, ourselves, were chipping the axe blade. Now, for a very long time, our ancestors used a Julian ax, and that didn’t change for, probably, a million years. At some point, innovation kicked in, and if somebody thought of a new way of doing something, that could spread through the population. Of course, there is a limitation to how learning spreads culturally. You really need to be there to observe. Even with the development of speech, you had to be there in real time to tell somebody how to do something. So, the invention of writing was another point at which people were able to do things together on a scale that they were not able to do before. This is what sociologists call “collective action” in performance.

The origins of writing actually came from accounting. The symbols of agricultural civilizations enabled these large empires to emerge for the first time, with hierarchies and work gangs, and irrigation and large-scale building projects. The people who kept track of things, the priests or the rulers, began to make deals. If you deposited 50 bushels of wheat in a granary, they would get you 50 little clay tokens and make it into an envelope.

For a very

long time that persisted, but then the clay tokens became symbols. That was something called “exactation.” It is like adaptation. It is taking something that already exists and using it

for another purpose. All those things came from our deciphering the abstract meanings of a mark, and it may have come from looking at a print on the ground and knowing very quickly whether this means

there is a predatory issue to the mark, or whether there is something you may be able to keep, or if we should run after it.

How important is the notion of the tribe?

The question is about human evolution, which is why is it that we cooperate when the situation is highly competitive? Those people’s genes individually may not have an advantage, but the genes of that group will have an advantage. The group will be able to compete more effectively for resources in the environment. Whether they are competing with other animals or with other humans, the presence of cooperators in the group can lend them a kind of group survival capability.

Look at the Web. The architecture of the Web is such that it enables people to do self-interested acts individually that add up to a common public good — something that is useful to everybody. The principles and protocols were designed to enable individual innovation to spread.

So, we are kind of at a meta-media level here in which we are beginning to see media that are designed to enable new media to form. Conversely, you do not have to ask anybody’s permission to go on the Internet or the Web. You just follow protocols that work with this architecture.

Napster is a good example of an architecture that forces this kind of sharing. If you were out collecting music on Napster, you’re not going through a centralized server. You’re downloading it from someone else’s hard drive. And while you were downloading it, by default, the folder, the directory on your hard drive that you were saving music in was open to anyone else who was on Napster.

Are people joining more groups?

Each time we have new media, we also are able to do things together. On larger scales, where we were not able to organize before. And through speech we were not able to organize in places before. So, I think you can see this is a kind of a leitmotif in human, biological and cultural evolution. It is this ability to invent new ways to communicate. We use those new ways of communication, among other things, like more powerful forms of collective action.

Well, go back to [my book] Smart Mobs, I interviewed David Reed. David Reed was one of the architects of TCP/IP. He came up with something called Reed’s Law. Sonoff’s Law has to do with the value of a medium. Sonoff was one of the founders of broadcast television. The power of television is equal to the number of television receivers. The more television receivers, the more powerful television as a medium is, the more money it makes, and the more influence there is.

Then, there’s Metcalf’s Law. One fax machine is totally useless. Two fax machines are useful to the two people using them. If you’ve got a hundred fax machines, it’s a lot more useful because any fax machine can communicate with any other fax machine. This is how it goes arithmetically, with the addition of new units. Metcalf’s Law grows exponentially. It is the number of units squared, “squared” meaning you can communicate with every other one. So, it is the number of units x itself.

Reed came up with this idea of group-forming networks. A group-forming network is based on a Metcalf’s Law network, with every node being able to communicate with every other node. It is not just that every node can communicate with every other node; I can form a group with everybody on eBay who is interested in buying porcelain figurines. I can form a group with other political activists. So, that becomes exponential in the case of consumer nodes square. It becomes two to the power of the nodes. So, if there are 22, then, if it is N nodes, it is 210. So, it grows even more rapidly.

Do you see any modality in terms of our media’s ability to shift power?

I just finished a book about multiple literacies, for attention, participation, cooperation, crap detection, network awareness. Now, the people who have the most potential are the ones who are able to master multiple literacies. I don’t think we’re going to be able to see a universal multiple literacy. I think we’re going to see an increasing segmentation. There are five billion mobile phones, and two billion people on the Internet, but has to do with whether you know, or do not know, what to do with it.

You can get an answer to any question in one second, out of the air, practically anywhere on Earth. It’s up to you to interpret whether the answer is good information or bad

information, or disinformation. But an awful lot of people believe things, whether it’s political or urban legends, or, even more dangerously, medical information, and do not know how to find

their way. It’s not really rocket science, but it’s not really pop.

How do brands, or the companies that build brands participate in this?

With these networks of trust, I think it’s fairly easy to protect the trustworthiness of a brand. I guess you could argue that there are some brands that are associated with institutions that don’t really need trust. Now, does BP need trust? A lot of people don’t trust BP anymore, do they? On the other hand, during the spill, if you searched on “BP spill” or “Gulf oil spill,” you’d notice that British Petroleum was trying to tell its side of the story. So, for some reason, maybe it’s political, it was important to BP, even though we didn’t really have much of a choice there. If youdon’t like one brand of cookie, you’ll get another brand of cookie. You only have that choice of petroleum. Still, the trustworthiness of their brand is important to them.

The old advertisers said that you came up with a message and broadcast that message, and now there is more of an interaction with the consumer of that message. There is more interactivity. You are seeing a lot of this. There is a whole tribe of social media marketing consultants. It really boils down to that you not only have to listen to your customers, you have to communicate back with them. Maybe that’s where the reciprocity comes in.

Google was a machine built by engineers. They never had any use for customer service. They’re run by many people, but there is no customer service. Now they are becoming social. They’ve got Google+. There is this big conflict going on about real names versus pseudonyms. Suddenly, they are faced with having to respond. When they become social, you are not a machine anymore. You are social. I think they are faced with big problems. They better scale up some kind of customer service, or forget trying to be sociable.

I mean Facebook is notoriously not easy to get to, but things can be fixed when something goes wrong. It can be done. There is somebody who works for Facebook who

will help you with a problem.

As the type of media we use speeds up due to Moore’s Law and faster micro-processing, and we begin to move at hyperspeed, how’s that going

to affect our species?

The question is to what degree is the human brain adaptable through this explosion of available information, and to what degree is the increase in the pace of change possible? How do we live it? I think there is a combination of attentional framing and the use of information tools that I call “infotention,” which I’m actually teaching to people and that I’ve written about in my book. The technology affords distraction, but I don’t think, as Nicholas Carr wrote in “Is Google Making Us Stupid?”, that the technology makes you shallow.

I think it affords distraction, but that doesn’t mean you have to be distracted. It means that you’re going to need to learn to discipline your attention. You need to learn what to pay attention to, because there are a million times more choices at any point. So, again, it becomes a form of literacy and it becomes a skill. You literally re-wire a young human’s brain when you teach him or her to read and write. You’re forcing the brain mechanisms that were involved for different purposes and are not naturally coordinated to act in a coordinated manner. We’re not really seeing, yet, an organized attempt to train people to deal with it.

Great overview from an interesting fellow...

One correction: what you called "exactation" is actually "exaPtation." Here's an article I wrote about the evolutionary principle of exaptation and how it applies to the human creative process:

http://bit.ly/exaptationoftheguitar