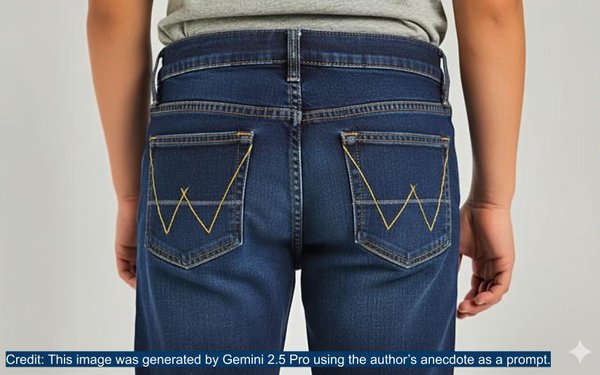

As a young boy, my family moved towns, and I

found myself in the unenviable position of having to find a new friend group. The first guy I met I thought was very cool. He had an awesome bike, and he was wearing Wrangler jeans.

I hadn’t thought about clothes before that, but suddenly, I wanted a pair of jeans – and they had to have a ‘W’ on the back pockets. Now, my mother was a little

thrifty, and she had a sewing machine, so she thought rather than buying jeans she would make them. The experiment didn’t turn out well. In a strictly defined way, they were jeans, in that they

were long pants made of denim, but the similarities to Wranglers ended there. I wore them once and never again. And from that moment, I understood the power of brands. The strange alchemy that accrues

trust in craftsmanship, performance or quality to a product but that also conveys something more intangible – a feeling that you will be happier, or more attractive, or less lonely because of

your purchase. I understood that brands were powerful things.

advertisement

advertisement

And yet, an anecdote that was shared recently by the Chief Commerce Strategist at IPG led me to question whether brands

were viable in the long term at all. The example he shared was from a specific category – Beauty – but it was a dynamic he had seen played out across categories, from packaged good to

electrical equipment.

In this instance, a faceless company had signed up as an Amazon reseller of a specific brand of beauty products – primarily topical creams to treat

wrinkles etc. But their goal wasn’t to make retailer margins on the sales, it was to measure which products sold most, and sold fastest, and then to gather the review data from those sales. With

that data, they would use AI to pinpoint precisely which aspects of the products people were searching for or enjoying - the percentage of Hyaluronic acid in the cream for example – and

then formulate their own, unbranded product with the ideal, data-driven formulation which they would sell on Amazon. The active ingredients would take the place of the brand name on the packaging.

They could complete the whole process, from research, to formulation to packaging to sales in less than six months – and sell millions of units.

For any brand marketer, this

would appear to be a doomsday scenario. You invest in research and innovation, you invest in building a brand over time, and someone swoops in with none of your overhead and usurps your product from

the digital shelf. The issue has been prophesized for some time. Marketing’s most famous Prof – Scott Galloway – has opined that we no longer need brands because we have reviews.

(Although in 2017 he also predicted that voice-based search would kill brands and that has yet to happen – in fact voice search has decreased slightly in the last few years.) More pointedly

perhaps, the dupe culture that has permeated on TikTok in the last couple of years where people gleefully share the leggings that are ‘just like Lulu but for a fraction of the price’ has

made it fun to find the unbranded deals.

But there is something short-sighted in sounding the death knell for brands. Dupes are, of course, duplicates of something that are

seen to have value. When someone says,’ they are just like Lulu’, they are tacitly endorsing Lululemon. (They may not be buying the product but, ironically, they are supporting the brand.)

And whereas online reviews can tell us whether the quality and workmanship of a product is good, that is the low-hanging fruit in the hierarchy of brand effects. Let’s say for example that my

long-suffering mother had been a world-class seamstress. The jeans she produced may have been fashioned in the same way as Wranglers, they may have been sewn from better quality fabric even, and the

seams and studs may have been indestructible, but would I have felt cooler when I wore them? Would I have felt like one of the gang? They remain the essential intangibles of brands and the

higher-order effect of long-term investment in brand building.

I wonder instead whether brands may begin to become more important again – both to us as individuals and to the

corporations we work for. Brands became commercially important in the middle of the last century when supermarkets began to replace mom and pop stores and shoppers had no one to rely on for advice.

Brands provided a way to navigate an overwhelming number of choices. And quickly, companies realized that the brand was the only leverage they had over increasingly powerful retailers. The

marketplaces are materially bigger now. And the choices are ever more overwhelming. And brands provide a way to navigate those choices, and they provide a degree of protection and leverage for the

brand owner. Sure, it is possible for us to do the research on every purchase by reading reviews on Amazon or watching YouTube videos – but who has the time to do that for everyday items, and

who cares enough?

So perhaps the truth is that brands aren't dying because they can be copied—they're thriving because they are being copied. Every dupe that promises to be 'just like

Lululemon’ is a tacit advertisement for Lululemon. Faceless Amazon resellers aren't killing brands; they're demonstrating their power by trying to replicate their magic. Inevitably though,

there’s something missing. As my mother's homemade jeans taught me, brands aren't about the stitching - they're about the story. And in a world drowning in choice, stories have never been more

valuable. Brands aren't irrelevant. They're irresistible.