TL;DR Mamdani won a landslide victory in the New York Mayoral

race because his campaign focused on progressive marketing theory not just progressive policy.

Although we rarely think about it, most everything we do is influenced by some

kind of theory. Sometimes those theories are well developed, explicit, and easy to articulate. More often, they are not. Instead, they are mental constructs that we build over time through a mixed bag

of trial and error, things we saw other people do, things we were taught at school or in college. The meals we make are guided by a theory of what constitutes a good diet. Our 401k investments are

guided by a theory of how wealth is developed. Theories guide us and consequently, it’s useful to give some thought to what theory we are applying to solve a problem or do a job.

advertisement

advertisement

There are several clear theories that guide advertising and marketing communications for example. And whether we recognize it or not we will be applying one or more of them to our jobs every

day.

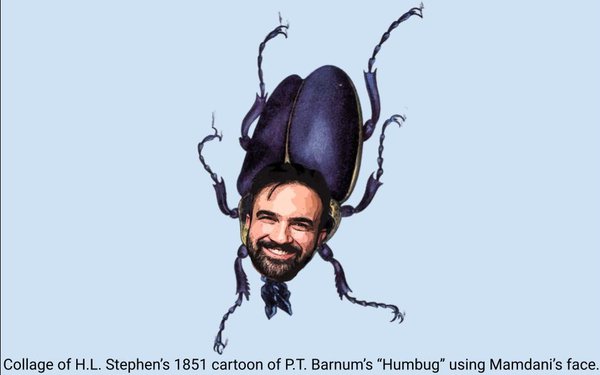

The noted advertising strategist and unofficial marketing historian Paul Feldwick outlined six theories of advertising in his book, "The Anatomy of Humbug." Those

theories, whether consciously or not, have guided our marketing practice since the early 20th Century. None of them are mutually exclusive and many of them coexist, but I find them easiest to remember

as three groups: Salesmanship, Seduction and Showmanship – and the dominant theory has changed over time.

- Salesmanship: persuasion,

"reasons-to-believe" - dominated marketing action through the early to the mid 20th century (and has made a triumphant comeback in performance media over the last 15 years).

- Seduction: the consumer insight, top-of-mind recall - started with the theories of motivational psychology in the 1950s and led to many of the most famous brands and

advertising campaigns of the late 20th Century.

- Showmanship: A throwback. The "din and tinsel" that made P.T Barnum famous. It was the bedrock of the early

PR discipline. And it is what is helping media-savvy politicians like Zohran Mamdani win now.

Successful political campaigns have mirrored these theoretical eras for

decades. Moving from rational political debate to emotional marketing appeals to outright political theatre. From selling policy to seducing voters to entertaining the electorate.

In

his 1928 race for office, Herbert Hoover treated his policy positions as products to be sold through detailed policy speeches and rational economic argument.

In 1984, Ronald Reagan

turned politics into a Pepsi commercial and won a landslide 97% of the Electoral College with a campaign built on the emotional promise of a new, “Morning in America”. (Not coincidentally,

the campaign was created by ad legends Hal Riney and Phil Dusenberry – the latter whom helmed Pepsi advertising at BBDO.)

And of course, Trump won his first victory in 2016 by

generating somewhere between $2 billion and $5 billion in earned media coverage through the orchestration of an unprecedented traditional, digital, and social media show. (Interestingly, in 2016,

Trump ran 323 rallies. In 1928, Hoover ran seven.)

Showmanship connects to the cultural zeitgeist and leverages it to create fame. It relies on energy, ubiquitous presence, and

provocation to spread simple, singular and authentic messages. The showman earns their place in the cultural conversation. They don’t need to pay to play and that gives them a massive

competitive advantage in media presence. And it’s why Mamdani just won NYC's mayoral race.

Mamdani, like Trump, implicitly understands the need for spectacle and

showmanship to capture the attention of the voting public. And he understands the need to anchor his theater with a simple, singular message. His platform was an affordable New York. It was an

authentic and believable position coming from someone who started his career as a foreclosure-prevention housing councilor in Queens. And everything he did, every show he put on, reinforced that

message in an entertaining, likable, tweetable way. He spoke to “Halalflation” demanding that Halal-cart meals return to the affordable price of $8 (while munching on a Halal-cart meal).

He spoke about rent freezes while doing the polar plunge at coney Island – dressed in a suit. His branding was distinctive, youthful, and memorable – purple and gold with bodega-sign

typography.

One week before the election he held a massive "briefing" for more than 70 content creators across Twitch, YouTube, TikTok, Instagram and Substack. They represented a combined

following of more than 77 million. Only one traditional media outlet was invited. Importantly, he built genuine relationships with the creators he worked with, refusing to treat them as free

advertising, he provided access, transparency and content opportunities galore – leading to organic social connection through the "Creators for Zohran" collective and the "Hot Girls for Zohran"

led by Emily Ratajkowski.

In doing so, he earned three times the social mentions and four times the social engagement of Andrew Cuomo in the last 30 days of the campaign. Drilling down on one

platform, he more than doubled his Instagram following in that time – adding over 4.4 million followers in a month. (By voting day, Mamdani’s Instagram following was 42 times larger than

Cuomo’s.)

Modern political races are being won by showmen. Those who recognize the shift from discrete events and emotional appeals to continuous content, real-time response,

and permanent performance.

Now, there may be cause for concern that this new kind of political theater is cheapening the democratic process, and that politicians may be

optimizing for algorithmic performance rather than public policy. Conversely though, it could be argued that this new, more accessible, more social political environment is bringing more people into

the democratic process.

One thing is clear; it’s not going to change. Any politician who wants to win needs to embrace modern marketing theory and practice. If they

don’t, they won’t. To use past as prologue, in 1956 Adlai Stevenson stood against the dominant marketing theory of the time and proclaimed that, “The idea that you can merchandise

candidates for high office like breakfast cereal is the ultimate indignity to the democratic process." He lost, spectacularly.