A fictional account of real-world technology

A fictional account of real-world technology

I lurched from the train car, elbow to elbow with a thousand other commuters stepping off New

Jersey Transit. I jerked my head to the right and heard a chime indicating my CPRS was online. A bright red arrow hovered in the air before me, analyzing the platform leading to the stairs going up to

the main platform of Penn Station.

“Go right.” Sean Connery’s brogue sounded in my brain as a red line appeared on top of the horde of pressing flesh all vying for the

same staircase. As I turned my head, the line flashed green when my best virtual path appeared before me.

IBM’s CPRS (Consumer Pattern Recognition Simulator) lets you set the voice

that navigated your actions through a virtual commuter game. (Connery’s voice had been chosen for me because I was a fanboy.) The app worked for any major New York transportation hub and was the

latest in IBM’s Smarter Cities offerings. It utilized image-recognition-based augmented reality (AR) to analyze results of multiple predictive formulas to create algorithms based on commuter

behavior. The game played out on my iPhone8 contact lenses.

“What arrr yoo prepared to dooo?” Nice. Connery’s quote from The Untouchables.

I headed

toward the stairs. In my urgency, I bumped a woman next to me, and she grunted. In the upper right hand of my vision, I saw my points decrease on a small New Jersey Transit icon.

“F**k!” I muttered, apologizing and letting her pass. In my ear, I heard the sound of a baby crying, and my points dropped even further. The AR in my contact lenses analyzed her past 50

tweets and discovered she was pregnant. Son of a bitch.

Everyone’s actions in the game were tied to real-world penalties and rewards. Early social-based action apps like Recyclebank

and DailyFeats were still in use to encourage people to earn free stuff or gain social cred. But apps like Gympact where, by choice, you were penalized by your peers for not going to the gym had

become wildly popular. Geek-chic went from craving Klout to demonstrating your accountability, and the craze had caught on with local government and utility companies. For instance, I regularly did my

laundry at three in the morning to get a high ABI (accountability based influence) score from Opower, the leading social network based on the Smart Grid.

And in my case, my next

month’s commuter pass would cost about 50 cents more because of bumping a pregnant lady. So now I had to make up my points via speed. I started walking fast. A heart-shaped icon appeared in the

upper left of my vision as the pulse monitor watch grew snug on my wrist. If the heart went from red to purple, my doctor would get a text indicating I was at risk for cardiac arrest. The monitor went

all the way to magenta four times one month, and my insurance premiums increased.

Once at Penn Station, I headed for the stairs, noting the commuter-gamers outside Starbie’s.

(Certain SIMs let you order your coffee mid-play, so you could pick it up right away and mobile-pay.) Distracted by the aroma of fresh-brewed coffee, I stumbled on something large at my feet. I looked

and saw a large sack of grain. A money icon appeared in my vision over the bag, so I pulled my eyes to the left, indicating I would take the points for the grain. Frustrated by having to wait for the

points to tally, I kicked the sack, hard. Then I ran upstairs.

As I neared the middle of the station, a red stop-sign icon filled my vision. I paused, not sure what was happening. Virtual

Air Rights codes had deemed it unlawful for advertisements or any game component to trick someone when using augmented-reality-based app functionality.

I heard a new voice in my ear.

“Chuck, look up.”

This freaked me out as none of my voice-recognition software was programmed to speak unless I spoke first. And most of my SIMs used eye tracking or Microsoft

Kinect to recognize my gestures before I heard external voices in a game.

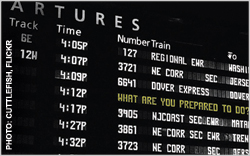

I looked up as I heard the board clicking, the shifting words forming the following phrase: All the world’s

a screen, and we are merely layers.

I stood for a long minute, gazing at the board and not really comprehending was what happening. I vaguely registered that my contact lenses were in

“reality” mode, meaning the board actually said the words I saw above me.

“You a Shakespeare fan?” The voice came again.

“Sure,” I said,

turning to see where the voice was coming from.

“Up here, Chuck.” I looked back at the board and one side of the screen was shaped like a smiley-face icon. The lips moved when

it spoke.

“Thought I’d go with a smiley face versus a scary Tron-looking thing. Besides, Tron Part Two sucked.”

“Agreed.”

“They

call me the Bard. A few years back, MOMA did a real-time data exhibit thing, and they ran Shakespeare quotes on my screen. Somebody got cute and took the ‘o’ out of ‘Board,’

and it trended on Twitter, so here we are.”

I looked at the other side of the screen, opposite his “face.” “So what’s with the quote? Am I a ‘mere

layer’?”

I assumed the metaphor had to do with the Smart Grid, where the notion of Big Data meant that with networked Artificial Intelligence, we’d arrived at an Internet

of Things mentality. In a sense, everything with a chip in it was alive, or in this case, a layer. Being a geek, I’d felt the whole idea (Singularity) was inevitable, starting around 2011 or so.

I was also sure Bard was hooked to the Internet and dozens of cameras in the station that pumped images he could access anytime from the cloud.

“Sort of,” Bard responded.

“Don’t get pissed, but I accessed your email and social channels just now.”

I wasn’t that pissed. “Privacy” had a whole new definition these days. Since

a GPS knew where you were at all times and everyone’s virtual games were hooked real time to the Web, government types simply accessed video or Outernet feeds from citizens whenever they wanted.

Everyone’s lives were recorded at all times. According to CNN, no event occurred without at least two cameras recording what happened for potential public usage. News and law enforcement had

become whole different animals the past few years.

“Why is my foot wet?” I said, interrupting Bard as warm liquid seeped onto my right foot. I looked down to see my black

loafer had a dark stain.

Bard spoke quietly. “That’s what I’m trying to tell you, Chuck. Look.”

His screen switched to an image of me arriving at

the platform downstairs from a few minutes ago. I saw my journey from the train and could tell I was in my game since my eyes appeared glazed and distant. The camera views switched a few times, from

commuters to station cameras and back. And then as I turned a corner, I saw myself stumble where I had kicked the sack of grain.

But it wasn’t a sack of grain. It was a homeless guy.

He had blocked my path and I had stumbled hard into his arm. And then I watched in horror as I pulled my foot back and kicked him squarely in the face, breaking his nose. Blood poured onto my shoe as

he clutched his face in agony while I simply took a step back while my points tallied.

“You weren’t supposed to kick the grain, Chuck,” said Bard. “That’s

what the money signs are for. Kicking good things means you lose points. But you were too fast. And Tom sat up at a bad moment.”

I couldn’t move. The image of me kicking the

homeless guy — Tom — kept playing over in my brain. It was an image I knew I’d never erase. And it wasn’t a game.

What kind of man am I?

I stood for a

long moment, game-blinded commuters rushing by. For once I heard the sound of shoes on pavement — no soundtrack, no sound effects. This was reality. And it sucked.

“Chuck.”

I looked up. Bard had cleared his screen, and the following words appeared slowly, one by one:

What are you prepared to do?

About a

year later, on my birthday, Bard said he had a surprise for me.

“Turn on your CPRS game.”

I did, and my commuter SIM went live. Bard had hacked it so it

was pointing downstairs, and I followed the arrow to the spot where I had kicked Tom. Instead of a sack of grain, I saw a huge virtual package with the words “The Impossible Idea” written

on the side. An icon on the upper left of my vision flashed, indicating it would open if I moved my eyes quickly to the left.

My Impossible Idea had been fairly simple. I quit my job and

volunteered at the Robin Hood Foundation to create an app that rewarded people for kind actions to the homeless in New York City. Gwyneth Paltrow was their spokesperson and with her avatar in the SIM,

the game took off. Starbucks joined in, and pretty soon the pay-it-forward mantra went full swing in Penn Station. Within a few months, people donated their Klout perks and accountability bonuses so

that actions generated behavior change as well as words.

So now I looked at the spot where I had kicked Tom, my life transformed by a mistake. I moved my eyes to the left, and the virtual

package fell open.

And I saw Tom. He was clean-shaven, waving and smiling. He was piped in via Skype, wearing the Robin Hood T-shirt they’d given him the day we first met. He’d

gone from being a volunteer to a full-time staff member, and gotten the first assisted-living residence made via profits from my app.

I smiled. “Thanks, Bard.”

Staring at the spot, I blinked three times rapidly to turn off my SIM’s contact lenses. My vision cleared of all icons, layers disappearing between me and the empty pavement where Tom used to

lie.

And it was empty.

advertisement

advertisement