Countless critics have already filled their columns with praise for “Waterloo,” the midseason finale of AMC’s “Mad Men” and an episode so rich with plot, character

advancement and remarkable dialogue that I find myself thinking it must be contemplated and discussed for days or even weeks in order to fully appreciate all that it offered. The experience of

watching it and then thinking about it is not unlike that of appreciating a great movie -- one that with reflection, continues to take shape, challenge and satisfy over time.

The impact of “Waterloo” would seem to suggest that we think of the first half of the final season of “Mad Men” as a seven-hour movie -- one with

an unforgettable ending. Five days later I still don’t know what to make of Don’s vision of Bert dancing with a bevy of beautiful secretaries while crooning “The Best Things in Life

Are Free.” I have enjoyed reading the thoughtful responses of others to this entirely unexpected sequence almost as much as I enjoyed watching it.

advertisement

advertisement

Isn’t it great to have a scene

from a dramatic series become one of the most talked-about television moments of the year without anyone getting threatened, beaten, shot, beheaded, disemboweled or otherwise slaughtered? It has been

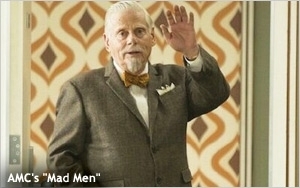

and will continue to be processed differently by each and every viewer, but that makes it an all-too-rare-gift. The fact is, Bert’s performance was greatly moving for Don and something of great

joy for the rest of us. And it has to be one of the best farewells ever written for an actor in a television show (in this case Robert Morse).

Bert’s song and dance was one of many memorable moments that made “Waterloo” the strongest hour of “Mad Men’s” half-season. The most profound were the responses

of all of the characters not simply to the reality of a man walking on the moon but their ability to watch it live on television. Each of their varied reactions was informative and accurate, including

the remarks made by teenagers Sally and Sean about trips to the moon being a waste of money while people were suffering on earth -- though I recall hearing more adults than kids express that

opinion.

Those of us who remember experiencing the moon landing -- even as kids -- instantly recognized the sense of wonderment that struck Don,

Peggy, Bert, Roger, Betty, Henry and their families and friends. The conversations about it that followed, as well as the opening of Peggy’s last-minute Burger Chef pitch the next day, perfectly

captured the immediate and lingering magic of a genuine shared experience that enthralled millions of people all at once. There have been many shared television experiences since, but they have

generally involved disturbing events. As for the singular magic of the moon landing on that July day in 1969, “Mad Men” nailed it.

So much happened in the episode that one might

say it offered something for everyone. For me, the top moment didn’t involve Bert’s production number (a nice counterpoint to the grumbling by Sally and Sean) or the moon landing -- it was

hearing Peggy talk about the dynamics of the family dinner table in her pitch, specifically her mention of the television always being on during dinner with the continuous coverage of the Vietnam War

on the evening news playing in the background. (The entirety of Peggy’s pitch may have comprised the most beautifully written dialogue of the entire 2014-15 television season.)

If I have

had one primary issue with “Mad Men” in recent seasons it has been with its rather cursory treatment of the Vietnam conflict, as it was known in the day. I realize the show is about the

lives of specific people, and that executive producer Matthew Weiner and his team go to extraordinary lengths to keep them interesting and engaging within their worlds. But I remember even as a kid in

the Sixties that Vietnam was top of mind with everybody everywhere and at all times, and I haven’t felt much of that watching this show. As Peggy so accurately noted, families watched coverage

of the war together every night during dinner (the Sixties being a time when families still sat down to an evening meal together, even with a television set nearby). Children asked parents about it.

They also asked their teachers to explain it. Parents talked with clergy and with other parents about it, often worrying about the futures of their young sons as the war continued on. The arrival of

the afternoon paper every day -- still a huge event back then -- brought fresh horror stories within. The same was true of the weekly arrival of Life magazine, which everyone devoured,

including kids.

But with only occasional exceptions the characters in “Mad Men” have often felt as removed from the war in Vietnam as real people in recent years have been from the

wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. That is to say if people haven’t been directly involved, or suffered a direct loss, or known someone who has served, then those two wars really haven’t

permeated their lives -- not in the way Vietnam permeated everyone’s lives in the Sixties. The media had everything to do with that.

Regardless, for me any and all such concerns were

swept aside when Peggy said what she did in her magnificent Burger Chef moment. How appropriate that “Mad Men,” one of the finest shows in the history of television, should elevate the

medium once again by reminding us that sometimes a line or two of expertly written dialogue can put across more history, drama and emotion than many extended scenes that address similarly substantial

subjects.