Nearly two decades after

the ad industry finally began shifting from its reliance on “last click attribution,” a new, equally short-sighted push is being made that could overweight the importance on the last

moment of advertising cognition. I’m dubbing it “last cognition attribution.”

I’ve seen the movement gathering steam in recent years as a gold rush of

so-called “attention metrics” suppliers has been racing for dominance of the new cottage marketing research industry, while simultaneously conditioning advertisers and agencies that

“attention” is what matters most in advertising.

That’s an appeal that seems intuitively logical when you utilize your sapien brain, but after nearly half a century

of covering advertising and marketing, I’ve learned from some of the smartest people in the business that sometimes the most effective advertising utilizes our mammalian brains, or even our

lizard ones.

advertisement

advertisement

It was one of the first principles I learned when I got to interview legendary Doyle Dan Bernbach ad man Tony Schwartz as a cub reporter in the early 80s. Schwartz, most

famous for creating the “Daisy” spot credited for helping Lyndon Johnson defeat Barry Goldwater in his 1964 reelection bid – you know, the one featuring an innocent little girl

pulling the petals of a daisy, as a nuclear bomb explodes in the background – worked because it connected with us an a subconscious level.

And when I finally got ot interview

Schwartz, he explained that any great ad – or for that matter, great storytelling of any kind – works best when it “taps into things we have already stored in our mind.”

And some of those are ancient things that helped us survive and evolve to the point where our brains got so large and sophisticated that we could begin attributing things to the last thing we were

cognitively aware of.

This is not a takedown of attention metrics, per se. There’s a lot of good work being done by that supply chain, especially the ones that are utilizing

sophisticated biometric measurement and applying neuroscientific principles that also implicitly include unconscious and pre-conscious factors. Or if I may, the whole egg of a human experience.

The problem is some of these attention metrics suppliers aren’t really doing that. They’re simply relying on methodological approaches that attribute ads that yield a response

based on some measure that people actually paid attention to it.

And to me, that is the neuro equivalent of last click attribution. So let’s call it what it is: last cognition

attribution. And let's agree that’s only a part of how advertising actually works – sometimes, the lesser part.

But there’s some potential good news on the horizon

and, not surprisingly, it is coming from the ad industry’s research authority, the Advertising Research Foundation (ARF).

It’s called the “Attention Validation

Project,” and it will be unveiled this afternoon during the ARF’s “Attention

2022” even in Brooklyn.

The goal of the project is to validate the claims being made by the litany of attention metrics providers – what the ARF calls

“synthetic measures of attention,” based on machine learning, AI, and processing – by applying neuroscientific validation so advertisers and agencies have some baselines for

validating and comparing attention metric suppliers, especially those that are trying to create weights for the ad industry to pay premiums when buying certain media. (I know of at least one so-called

metrics supplier that calls itself “research,” but makes its money by selling the ad inventory that its methods identify as having higher attention values, which isn’t exactly a

transparent way of doing business.)

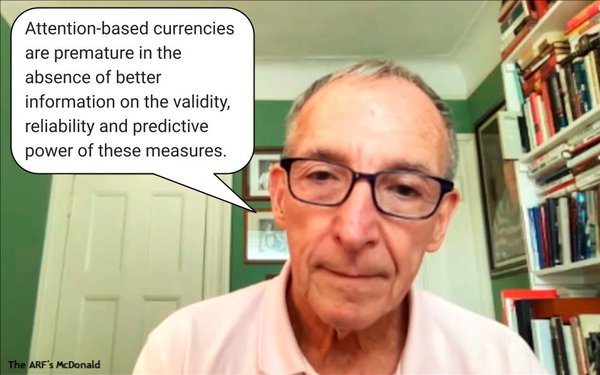

“Recent years have seen increasing interest in direct measures of cognitive and emotional response to advertising,” ARF CEO and

President Scott McDonald says in a statement announcing the validation project.

“As a result, a number of new services have entered the marketplace with different approaches to

the measurement of attention and/or emotional responses to ads. This excitement has caused some to push for incorporating these measures into next-generation currencies for media buying. But, we still

don’t know enough about the reliability and validity of these measures and their rightful application to advertising and media evaluation. It is the ARF’s view that these discussions of

attention-based currencies are premature in the absence of better information on the validity, reliability and predictive power of these measures. That’s what this study seeks to

address.”

Kudos to the ARF for getting out in front of what could be Madison Avenue’s next new attribution war, and for applying some legitimate science to it.

I hope you pay attention to it. Or if not, that you embrace it some unconscious level.