From all my

years in research and consulting, I think I’ve learned a thing or two about marketing worth sharing. Enduring fundamentals, mostly—yet often overlooked. So, over the course of my biweekly

column this year, I want to share some snippets for your consideration. I hope they’re helpful.

This week’s thought: Consumer opinions are mushy.

The core idea of marketing is consumer-centricity, the foundation of which is knowledge about consumers. Which means that marketing is steeped in data about consumer opinions. Yet, much of

these data masquerade as verity. Because consumer opinions are mushy.

Not all the time. But lots of the time. This is no secret. It’s an issue that researchers have struggled

with since the beginning of polling and survey research. But it is not something typically acknowledged or factored into marketing.

advertisement

advertisement

There is an inherent bit of mushiness built into

every survey result. Some portion of the respondents to a survey know or care little about the issues being surveyed. Yet, most analyses treat responses from every respondent as equally reliable. The

question of mushiness is rarely assessed. Mushiness can be a big problem if it is characteristic of most respondents to a survey. Even a small number, though, can render conclusions about consumer

opinions undependable.

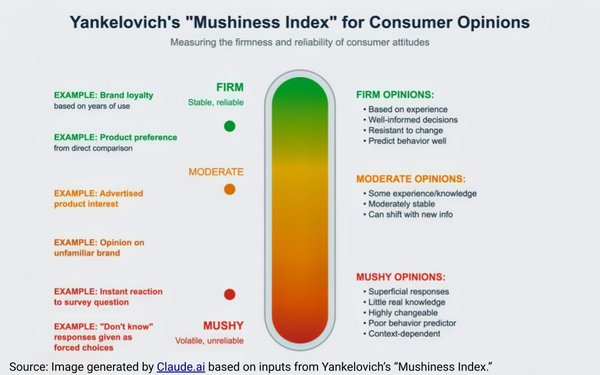

Dan Yankelovich, founder of the firm I worked for and ran in years past, tackled this problem in the early 1980s with something he called the Mushiness Index.

An extensive, two-year, research-on-research project underwritten by Time magazine led to the development of a four-item battery able to determine if public opinion on an issue was mushy or not.

At the time, the firm conducted the Time public opinion poll. The original plan for Dan’s Mushiness Index was to visually signal the degree of mushiness in the Time polling results.

It was hoped that this would not only improve those polls (and thus add some luster to the Time poll). It was hoped to set an example for other polling firms to follow as well. Unfortunately,

circumstances intervened, and this plan did not happen.

This was an opportunity lost. As time has gone by, the problem of mushiness has faded from the professional conversation that

researchers, marketing researchers in particular, have with themselves. It never occurs to marketers that carefully collected survey data might rest upon answers respondents provided only because they

were asked, not because they know anything or care about the topic.

It’s worth remembering that most respondents these days come from survey panels that compensate respondents

through various currencies to participate in surveys. When respondents are paid to express opinions, they will do so whether their opinions are mushy or not. To collect their reimbursement,

respondents will answer anything we ask them.

Marketers must remind themselves that consumers do not care as much as marketers do about brands and advertising. Asking detailed

questions about things not central to people’s lives runs the risk of generating mushy data. Which is not a strong foundation for business.

Dan was philosophical about the

failure of mushiness to catch on. Years later, in retrospect, he said he had come to realize that journalists were never going to embrace something that marked a poll as inconclusive or unclear. Doing

so is at cross-purposes with journalists looking for conclusiveness about a hidden truth. A similar conflict is at the heart of marketing.

Mushiness is not just about signifying the

reliability of answers to a survey. Mushiness also reveals another layer of insights into consumers.

For example, marketers still struggle with the so-called value-action gap between

sustainable attitudes and green behaviors. This gap is easy to understand once you realize that most environmental attitudes are mushy. Broadly speaking, these are not firmly held values because, by

and large, they are not grounded in any sort of personal relevance. Which is the first of the four things that figures into Dan’s measure of mushiness.

The second thing that

figures into mushiness is the extent to which respondents feel knowledgeable. Dan’s original mushiness work found that higher self-perceptions of knowledgeability are predictive of more firmly

held opinions. When people feel they know a lot, they tend to be less diffident in their attitudes. It doesn’t matter if they know ‘correct facts,’ quote/unquote, or not. Just that

they feel knowledgeable. One lesson for the contemporary marketplace is that fighting ‘fake facts’ with counter-facts will always be a losing battle. There is nothing mushy to affect or

firm up. This lesson is just as relevant for brands as for politics.

But this doesn’t mean that incorrect beliefs cannot be corrected or improved. Dan believed that that

happened through deliberation, which has the added effect of firming up opinions. The third element of mushiness is the extent to which people talk about things with others. Of course, as we know from

our collective experience with social media, talking with others in an echo chamber leads to more extreme views not to views more accommodating of democratic compromise. This is not necessarily

desirable, but it is certainly less mushy. Politicians prefer voters who are unwilling to switch opinions. And marketers prefer consumers firm in their preferences. Mushiness means precarious footing

for brands.

Beliefs people admit they might be willing to change are mushy. This is the fourth element of mushiness. In the context of buying, many purchases are motivated by tacit

reasons, not by reasons that people can stand firmly behind. This means mushy. When attitudes are mushy, there is nothing to firm up resistance to competitive pressures. Even iconic brands are at risk

if attitudes about them are anything less than firm. Mushiness is a barometer of risk.

Not every question or issue is equally definitive in people’s minds and thus not every

survey result either. High brand ratings are great, unless they’re mushy. It’s the extra step to measure mushiness that tells us whether our results are a mirage of certainty or a sure

finding.