I collect T-shirts the way other people collect art or wine, but unlike them, I don’t preserve them for the future. I live in them to remember an important

experience they are associated with. I wear them until they are worn out and all that’s left is the memory of what they represented. So it tickles me when I see my 17-year-old daughter sporting

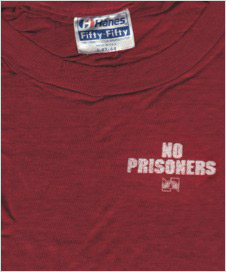

my 30-plus-year-old “No Nukes” T-shirt, or when I saw my son wearing the threadbare one shown in the image above.

I collect T-shirts the way other people collect art or wine, but unlike them, I don’t preserve them for the future. I live in them to remember an important

experience they are associated with. I wear them until they are worn out and all that’s left is the memory of what they represented. So it tickles me when I see my 17-year-old daughter sporting

my 30-plus-year-old “No Nukes” T-shirt, or when I saw my son wearing the threadbare one shown in the image above.

That shirt is special to me for

many reasons, but most importantly, because it was handed to me personally by late NBC programming chief Brandon Tartikoff in the spring of 1984, just after he briefed the affiliated station troops on

the peacock network’s new prime-time schedule. The shirt has an NBC logo with the words “No Prisoners” on top of it, and it conveyed the spirit Tartikoff had when I interviewed him

on his plans to turn the network around after another devastating prime-time season — and one in which some pundits had written NBC, and Tartikoff, off altogether.

advertisement

advertisement

Maybe it was just showmanship, or salesmanship, but I believed Tartikoff believed what he was saying to me when he outlined how the new schedule, with rookie series The

Cosby Show as its centerpiece, would put NBC back on top. History proved him right, and the experience, more than any other, defined for me what the upfront is really about: making bets. Big

bets, but calculated bets. And all the things I’ve been highly critical of over the years — the upfront’s smoke-and-mirrors spectacle, its antiquated market inefficiency, and

especially the media spin surrounding it — are the things I love about it. It’s all about the show, and if you pick the right ones, you’re back on top.

We’ve dedicated this issue of MEDIA to examining the upfront — both the economics of its market structure, as well as the unique role it plays in the

culture of our industry, and our society at large. It’s the closest thing Madison Avenue and Broadcast Row have to Hollywood’s dream factory, where the spin and sizzle are as much a part

of the product as the product itself. But as the old Madison Avenue adage goes, nothing can kill a bad product faster than good advertising, so goes the prime-time upfront. But for every

Manimal or Super Train there is also a Cosby. You just never know until the viewers actually weigh in.

The part I like the least about the upfront,

is the clubby, incestuous nature of how business gets done. And if you wonder why I’m so cynical about it, it is embodied by another adage I heard just after I started covering the upfront, and

it’s one that’s still used today: “No buyer ever got fired for paying too much in the upfront, but some have lost their jobs for missing the upfront.” The “missing”

is a reference to the timing of the market, and the fact that buyers who don’t move fast can get left holding the bag, missing out on commercial time in the best shows and/or paying too much for

them. It’s the kind of logic that is a nostalgic throwback to an old world of doing business in this age of programmatic buying and agency trading desks, but that kind of thinking is still

pervasive among media buyers, and advertisers too.

I miss the days when a programmer like Tartikoff could make a few bets and transform a schedule, a network and

prime-time television culture. I don’t miss the old-school way agencies buy the upfront — because, like my faded T-shirt, it lingers on.