Tomorrow will

mark the one-year anniversary of one of the most heinous and unsettling crimes in American history – the mass murder of twenty children and six adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School in bucolic

Newtown, Connecticut.

If you were to take a stroll this afternoon through the center of Sandy Hook, a charming hamlet located within Newtown, you would notice dozens of signs printed in big (some

might say angry) red letters posted around town, all issuing the same warning: “No MEDIA. Police take notice.” These signs are the work of residents who are determined to avoid the kind of

extended media invasion this weekend that compounded their grief last December. According to published reports, local police have decided to enforce the signs.

Who can blame them? While I

certainly can’t claim to have been directly impacted by the horror of the murders, I live close enough to Newtown to know a number of people who were, and I remember how distressed they were by

the Great Media Invasion of Sandy Hook. Admittedly, I’m more sensitive to how the media handle coverage of tragedies after living through two such events during the last two years: The

devastation of coastal tri-state communities, including my own, that took direct hits from Hurricanes Irene and Sandy. My waterfront home in New Haven County was somehow spared in both storms, but

there remain reminders throughout my neighborhood that others weren’t so fortunate. The media coverage of Irene was absolutely abysmal, which seemed only to make matters worse around here. The

coverage of Sandy was much better.

advertisement

advertisement

My primary memories of December 14, 2012 involve watching hours of breaking news coverage on broadcast and cable news channels from the area surrounding

Sandy Hook -- most of it inaccurate until much later in the day, when the actual details of what had happened were properly reported. At the time the media’s immediate handling of the story

seemed unforgivably insensitive, especially in the matter of the murders of so many children. In hindsight I tend to think that I may have judged the media too harshly; after all, the terrible events

about which they were reporting were the stuff of unthinkable madness and confusion. Still, I remember feeling decidedly ill-informed for much of that day, despite all the TV I watched.

On the

night of December 14 I met friends at a local pub to talk about what had happened. The pub was filled with people who wanted to do the same thing. They needed face-to-face contact rather than whatever

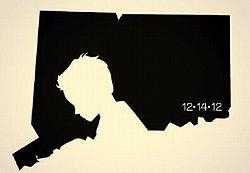

comforts social media can provide. Most of them had been at work during the day and hadn’t experienced the full media rush of it all. The haunting image at the top of this column was circulated

through the pub that night via smartphones. I don’t know who received it first, but throughout the night almost everybody in there saw it on someone else’s phone and asked for a copy. I

don’t know the origin of the image, but one year later it still says more than any words or video can express.

Earlier today I talked with my old friend and former colleague, the veteran

journalist and media observer John Motavalli, who moved to the Sandy Hook area with his wife Nancy in the late Nineties. Today as twelve months ago, Motavalli spoke with great passion about the

prolonged intrusion of the media in the wake of the murders and the impact it had on his beloved town. Sandy Hook is situated around one central intersection, which was largely impassable for days

once it filled up with cars and trucks transporting reporters and camera crews representing media outlets from all over the world. There was little regard for residents who needed to get around.

“I waited for a week after it happened,” Motavalli recalled. “Then I went into town and I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. The media were so annoying and disrespectful.

They had taken over the town! Crew members were laughing and joking as if nothing terrible had taken place.”

At one point Motavalli snarled at a random cameraman, “You’re all

a bunch of vampires and leeches.” There was no response.

Motavalli went on to confront reporters he encountered on the street. “You aren’t fulfilling any purpose here other

than to get ratings,” he told them. “There’s no story anymore. What are you still doing here?” Some of the reporters ignored him. Others attempted to pacify him without

success.

It’s one thing to offer hindsight comments about a past experience. It’s quite another to read words that were committed to record during the experience itself. Here is an

edited excerpt from a Facebook post by Motavalli immediately following his experience with the Great Media Invasion of Sandy Hook:

“I drove home yesterday at around 3:30 and couldn't

reach my house … There was a kind of carnival media circus going on. When I left in the morning, I saw all the camera crews and the set-ups and the like. As someone who used to be involved with

media, I was sickened by the whole thing. It reminded me so much of a Kirk Douglas film called variously ‘Ace in the Hole’ or ‘The Big Carnival,’ directed by the great Billy

Wilder. In it, Douglas plays a down on his luck reporter working on a jerkwater paper in a small New Mexico town. A guy falls down a mine shaft, gets stuck there, and the reporter makes it into a big

media event, his ticket back to Pulitzer Land. The town is turned upside down as a result. The same precise thing is happening here. But it's worse than that.”