Al Franken and Donald

Trump have one significant thing in common: They both made their bones in the television business before taking up careers in politics.

Like their political parties and points of view, their

TV work was quite different -- one a reality-TV star and the other a “Saturday Night Live” writer who parlayed his fame as a comedy writer to becoming a recognizable star on-camera on

“SNL” (most notably for playing the recurring character Stuart Smalley).

He also became a frequent guest on various late-night talk shows where he emerged as a wit who could carry

on conversations worthy of late-night TV.

Now he is gaining a measure of fame as another in an increasingly long line of public male personalities accused of sexual harassment in some form or

another.

advertisement

advertisement

Senator Franken was accused of forcibly kissing Leeann Tweeden -- a model, sportscaster and sometime Fox News Channel personality -- in 2006 when they were both on a USO tour in the

Middle East. Tweeden leveled the accusation last week and Franken apologized.

A photo emerged of Franken appearing to touch Tweeden inappropriately while she slept. In the photo, his hands

appear to be on her breasts and he seems to be leering. The aim of this very ill-considered photo might have been comedic because, like it or not, this is what comedians do (which is not to excuse

this behavior, merely to try and explain it).

But this is 2017, and Franken isn’t Bob Hope. So Franken's in deep doodoo. It's still too early to tell if he can weather this scandal

without having to resign.

Like the rise of Donald Trump, the Franken sex-harassment story is reviving memories of what it was like to cover Franken when he was but a lowly TV star and not an

august lion of the Senate.

I got to interview Franken only once, in March 1999. He was grouchy because the sitcom in which he starred (and had also created and produced) had just been

cancelled by NBC.

The show was called “Lateline,” a newsroom spoof in which he played a gung-ho but bumbling correspondent for a late-night news show modeled loosely on ABC's

“Nightline.” NBC had just given it the axe and Franken had an axe to grind.

I was surprised when an NBC publicist agreed to put me on the phone with him because the interview

that resulted was in no way beneficial to the network. Franken was furious and in no frame of mind to spare anyone's feelings. Instead, he unloaded on the network and the then-president of NBC’s

entertainment division, Scott Sassa.

“We made good shows,” Franken said. “I think NBC did a bad job in presenting it to the public,” he said, referring to the way

“Lateline” had been scheduled.

Premiering in March 1998 for just six weeks and then going away for a year, “Lateline” returned in March 1999 for a planned run of six

more episodes. But five of them never aired after NBC cancelled the series the morning after the first one attracted one of the smallest audiences ever recorded by the network on a Tuesday night up to

that time -- 6.7 million viewers.

“I felt cold-cocked. … [Sassa] promised me six shows,” said Franken, who characterized Sassa's “promise” as “an explicit

guarantee” that “Lateline” would have a run of six episodes to get on its feet.

“[Sassa] didn't explain why he felt ethically that you can promise six and then pull [a

show off the air] after one,” Franken complained. (At the time, NBC denied Sassa made any such promise.)

Franken then noted that it was unfortunate for the television production

industry in New York for “Lateline” to be cancelled because it was one of only a handful of situation-comedies then being produced in New York City.

He then unloaded on me when it

became apparent that I could not recall in that instant which other sitcoms were produced in New York. As a result of this shortcoming, Franken basically called me an idiot.

I tried to

explain to him that the identities of the other made-in-New York sitcoms (they turned out to be “Cosby” on CBS and “Spin City” on ABC) were irrelevant to our story. And if

they were relevant, I told him, then I would endeavor to report them correctly before the story got into print.

The main concern for me, as with any journalist, is not necessarily to have

every fact correct when you are interviewing a newsmaker and researching a story (although it certainly can’t hurt). What matters much more is getting it right by the time the story is

published.

And I assured Franken it would be correct, although by this time, he had had enough of me and I had had enough of him.

My story, headlined “Franken burns NBC

bridge,” published on March 22, 1999, was a great story for me, although I never learned how Franken felt about it. He never had another sitcom, choosing instead to enter politics. He won

his Senate seat in 2008.

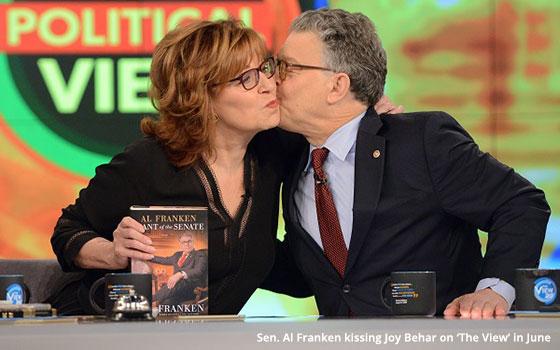

Photo of Al Franken and Joy Behar on “The View” last June courtesy of ABC.