When I was studying journalism in college in the late 1970s,

it was when a philosophical shift was taking place about how to cover news. Instead of striving to be 100% "objective," the new school of journalism (sometimes called "New Journalism") was that every

human being brings some subjective perspective to everything they do, and that it might be a good thing for journalists to put that filter on too.

I was fortunate enough to go on to work for

one of the pioneers of New Journalism, legendary editor Clay Felker, when he was editing Adweek in the early 1980s, and he engrained the value of subjectivity in me, because it is one of the

most valuable things someone can share with someone else.

Obviously, not all stories justify a journalist putting their own perspective into an article, but whether they try to or not, there

is always going to be some measure of subjectivity, even if it's just deciding what to report and what parts to leave out.

advertisement

advertisement

I've always tried to do a good job of telegraphing my subjectivity to

readers when I do that, but the past several years of coverage -- especially coverage of political media -- has caused me to question my own approach more than ever. That's probably because much of

what I've been covering has been scientific research about how the subjectivity of news reporting influences how people perceive the reality of the world around them.

Among the sources of that

research, has been the Pew Research Center, which today released a fascinating study showing the disconnect among

journalists and average Americans. As well as among journalists of different ages, and American adults of different political or demographic leanings.

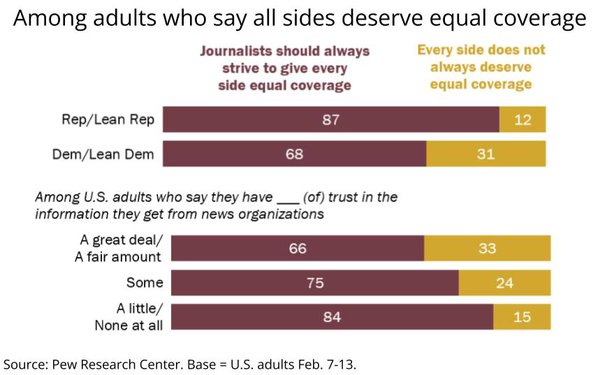

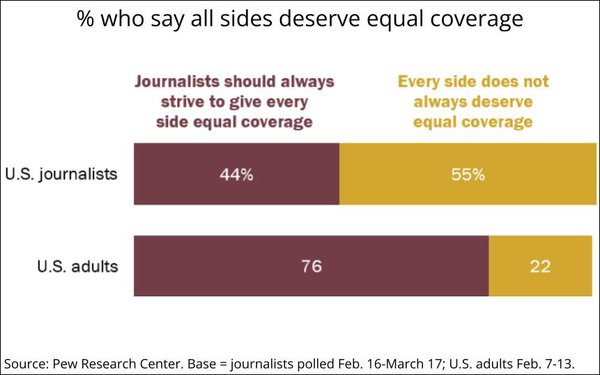

What it found overall is that

journalists are much more prone to believe that not all sides deserve equal coverage in their reporting than do average American adults (see above).

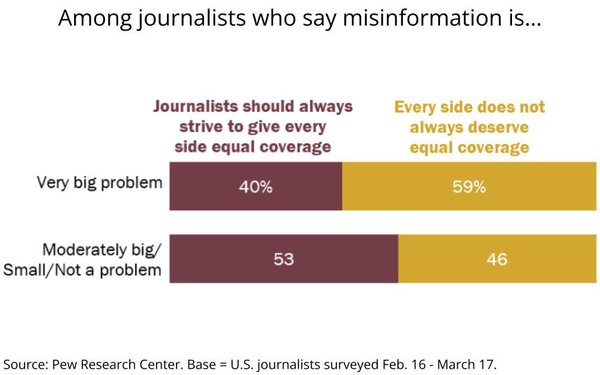

One of the main reasons for this divide,

write Pew's analysts, is that many journalists have grown cognizant of the role some sides play in spreading "misinformation." This is especially true among journalists who see misinformation as a

"very big problem" (see below). Full disclosure, if you couldn't tell by now, I consider myself one of those.

The problem with my disclosure is that some people will think I'm politically

biased, but I'm not. For more than 40 years, I have bent over backwards trying to report objectively on news representing different political points-of-view. And I think I've been more than

even-handed about it.

The bias I do have is about covering misinformation, especially the kind that might be characterized as gaslighting, or trying to get people to question their very sense

of reality.

I can name names, but you probably already know who I mean.

One of the problems is some of those sources of misinformation, also happen to be perceived as being heavily on

one side of the political spectrum (guess which one), and if you look at the tracking by Ipsos, Reuters, Axios and others, it's not just an opinion, it's based on some scientifically objective

facts.

Ipsos political expert Chris Jackson has done this several times over the past few years, utilizing objective facts such as COVD-19 science, to show there are explicit political skews,

and as he says, "alternate realities" in America. And journalists who bend over backwards to cover those alternatives equally are a big contributing factor in it.