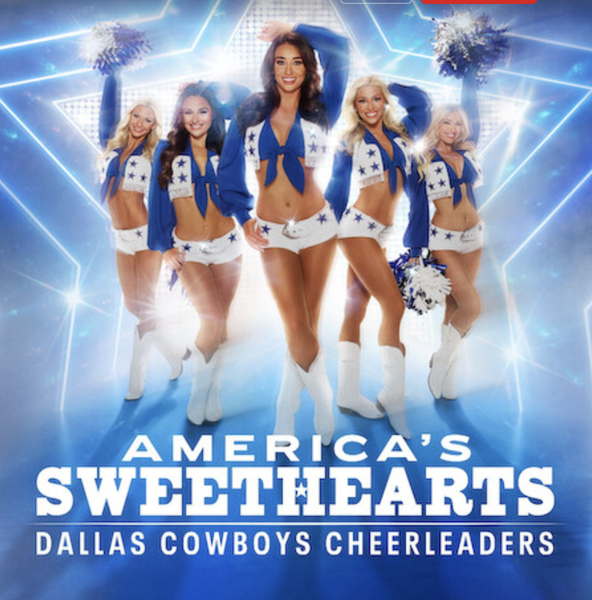

“America’s

Sweethearts,” a new Netflix seven-episode documentary series about the iconic Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, is a surprisingly tough watch.

That’s not only

because we see these would-be cheerleaders, who are all athletes and serious dancers, ages 20-24, go through grueling 12-hour days, a long and brutal audition process, a body-damaging training camp,

and three hours straight of performing in 96 degrees on game day.

But what’s harder to process is that for all the talk of sisterhood and “joy”

among the auditioning “girls” (who are never called women), they are psychologically tortured, their looks and bodies constantly harped on, 1950s style, by Kelli and Judy, the middle-aged

matriarchy of bosses to whom the cheerleaders report, and must uniformly answer with nothing more than “Yes, ma’am.”

advertisement

advertisement

I appreciate

that the director and showrunner, Greg Whiteley -- who also created the series “Cheer” and “Last Chance U” -- tries a more fly-on-the-wall approach here, to go

more than skin-deep. And it’s never about the camera focusing on cleavage.

But the sensibility is a paradox when not ironic.

That’s because the DCC org is backward-looking -- all about upholding “tradition” and standards going back to 1972. Indeed, the names for the

signature uniform might have changed, from hot pants to booty shorts, but the costume itself is still the same Hooter’s special.

There’s some dissonance

in this at a time of great progress for America’s female athletes -- getting more recognition, higher pay, more respect, and when more female athletes than ever will represent us at the Paris

Olympics. We’ve also made gains in diversity and body acceptance. It’s natural to wonder what has changed for the DCC, whose members are held to tough grooming and weight standards,

and whose moves and head tosses are designed to be sexually provocative.

It seems to be a self-selecting group, largely white and Christian. Many of the

girls talk about handing their worries over to the Lord. There are a handful of women of color, but seemingly no Asians or Hispanics.

Pretty early in the

episodes, one of the”veteran” girls is asked about the pay. She replies that it’s gone up. Now the salary is something akin to what a full-time worker at Chick-Fil-A would earn in a

year.

Certainly, the NFL cheerleader’s low salaries have been an issue for years. It’s as if these orgs operate on the antique supposition that the

ladies only need “pin” money, because they’re going to marry rich husbands.

On the pay issue, Whiteley rightly gives plenty of screen time to

Charlotte Jones Anderson, chief brand officer and daughter of Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones, to hang herself.

“There’s a lot of cynicism around pay

for NFL cheerleaders -- as it should be," she says, winding up for her “let them eat cake” blabbering.

“But the facts are, they actually don’t come here for the money.

They come here for something that’s actually bigger than that to them….There are not a lot of opportunities in the field of dance to get to perform at an elite

level…It is about a sisterhood that they are able to form, about relationships that they have for the rest of their life. They have a chance to feel like they are valued, they are special, and

they are making a difference.”

This from a woman who is co-owner of an organization worth more than $9 billion.

Possibly worse, one

former cheerleader mom says, “These millennials, X-Gen, whatever they’re called, they do look at it as a job, where us old-timers look at it as more of a privilege.”

There are other upsets: A 20-year-old newbie gets fondled on the field by a roving cameraman, while another has an air tag attached to her car. Both girls

notified the police and brought suits that were dropped for lack of evidence.

One of the girls, Victoria, whose mom was also in the DCC, develops an eating disorder,

not unexpectedly. And another, who completed her fifth year, is shown hobbling up at 25, using a walker, to accept an award at a veterans’ dinner. She’s had surgery for a hip displacement,

injured mostly from the difficult signature “Thunderbird” move of going from a high-kick line to landing in a full split.

Despite the long-term

injuries it causes, Judy the choreographer won’t get rid of the move because the split is a fan favorite. (Funny that Kate McKinnon’s Weird Barbie, with her crayoned face, spends all of

her time in the splits.)

Clearly, unlike what the boss’ daughter maintains, some of these women cannot go on to “make a difference” in their lives

or communities, hampered as they are by physical issues.

And the irony is that this coverage of the Cheerleaders will no doubt attract new recruits.

If only they could organize for proper pay and working conditions.