To better understand how

people are using generative AI, and to set the record straight for all the pundits weighing in on AI’s pros and cons, last fall, OpenAI released a study of 1.5 million ChatGPT conversations that

took place between May 2024 and June 2025. (Privacy protections were rigorously applied.)

The research team identified seven content clusters. Only the top three clocked in with

percentages in double-digits.

The two biggest were roughly equal at slightly more than 28% of all conversations -- practical guidance (e.g., tutoring, how-to) and writing (e.g., editing,

translation).

Next in line at just over one-fifth was the category of seeking information. It is in this latter category that shopping shows up.

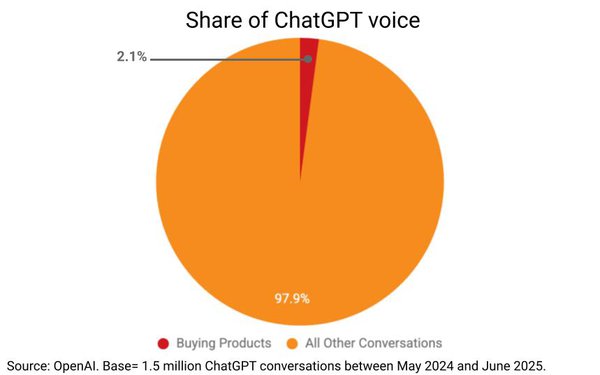

Conversations about

purchasing products were 2.1% of all ChatGPT conversations. Which raises a critical question for marketers trying to figure how to adapt to AI, and how fast. Is this big or not?

advertisement

advertisement

The

answer is that it depends.

One of the foundational concepts I teach in introductory data analysis is that there is no information value in one number. There is no way to know if a

number is big or small without comparing it to another number.

Now, this can seem counter-intuitive. We look at 2.1% and our gut reaction is to say it is a small number. But only

because we have an unarticulated, and probably even unconscious, point of comparison in our heads.

In the recesses of our gray folds, we might harbor the presumption that big numbers are 50%

or 100% or maybe 25%, and compared to that, 2.1% is small.

Which illustrates my point. We have to use another number for comparison, and sometimes we make this comparison without

realizing it. But we are researchers, or maybe numbers-driven marketers, so we must surface our assumptions and be very deliberate about our comparisons.

For example, if our ingoing

belief is that no chatbot conversations would be about purchasing products, then 2.1% is a strong bit of disconfirming evidence, assuming statistical significance (without so much power that we err in

the other direction).

Or if our ingoing belief is that AI is exclusively a high-tech shopping assistant, then 2.1% is a dearth of conversations offering no support for that working hypothesis.

Whatever the case may be, it is only in comparison that we can draw any conclusions about whether 2.1% is big or small.

And sometimes a number can be both big and small.

In July 2025, there were 18 billion ChatGPT conversations each week conducted by 700 million users, roughly 10% of the world’s population.

Do the math: 2.1% of 18 billion is

378 million. That’s seems like a lot of conversations. Then again, there are tens upon tens of billions of purchases each week worldwide, so maybe not such a lot after all.

What matters most is not the number itself but the benchmark or point of comparison, which should be relevant to the decision at hand. The benchmark should be chosen in advance of collecting

any data. The purpose of collecting data should be to assess results against the benchmark. Not collecting data just to see what you get -- because without a benchmark you won’t know what you

got.

Small numbers in the grand scheme of things are often big enough for critical mass. Small, but plenty big.

We know this from segmentation. A small segment may still be

big enough to support a special variety or design for that target group. That’s critical mass. This sort of benchmark is usually financial -- not small versus big, but big enough or not for

profitability. This is a pertinent metric right now for AI.

Headlines are full of the news that generative AI is not yet a profitable enterprise for AI providers. Yet, client

companies are jumping head-first into the deep end of the AI pool. Too small for AI providers but big enough for every other company. Because these companies see that 378 million conversations are

enough to build a business, and also more than enough to erode existing businesses and brands.

On the other hand, it is a reminder that AI is not about shopping. Because 97.9%

of conversations are about something else. AI can be deployed as a shopping and marketing tool, but that is just a commercial twist on a technology this is overwhelmingly about DIY self-improvement --

learning, fixing, connecting -- not buying. This is the bigger threat to brands.

As I’ve written many times quoting Ted Levitt, the late Harvard guru of modern marketing,

brands are in the problem-solving business. What we see in the research into ChatGPT is that, first and foremost, AI is in the problem-solving business. Who needs a brand when you can get the solution

from AI?

Brands worry that AI will recommend some other brand to buy as a solution. Which is a legitimate concern. But for many needs, AI may just be the solution. Now,

obviously, many such solutions will require tools and materials and ingredients, so brands will still be part of the mix, but only secondarily.

To say this another way, brands are

worried that AI will disintermediate them from the consumer shopper journey. By this way of assessing AI’s threat or benchmark, the 2.1% is big. But this focus on AI overlooks all that’s

going on with AI about lifestyles, which overwhelmingly makes the 2.1% is small.

People want AI for their lifestyles, and only a little bit for shopping. It’s in this role as a

lifestyle advisor and companion that AI will shove brands aside.

AI is taking over what marketing has always claimed as its purpose and value. This is what’s so big about AI—the

transformation of lifestyles, not the transformation of shopping.