The Media Kitchen owes its success to eclectic staffing, strategic insights and a thoroughly entrepreneurial culture

If a good friend or respected colleague were to ask me

to recommend a good place for their son or daughter to start a career in the advertising business, I would probably recommend any of the organizations being recognized in this

issue. But if one of my own children were to ask me, I would tell them to try and get a job at The Media Kitchen. The reason is that it has one of the best cultures for understanding the future of

advertising and media, and is organized in as likely a way as I can imagine to achieve it, or at the very least, in a way that will enable the people who work there to participate in it.

If a good friend or respected colleague were to ask me

to recommend a good place for their son or daughter to start a career in the advertising business, I would probably recommend any of the organizations being recognized in this

issue. But if one of my own children were to ask me, I would tell them to try and get a job at The Media Kitchen. The reason is that it has one of the best cultures for understanding the future of

advertising and media, and is organized in as likely a way as I can imagine to achieve it, or at the very least, in a way that will enable the people who work there to participate in it.

advertisement

advertisement

I’m not alone. When the agency pitched the media services account for financial services giant Goldman Sachs in early 2012, it won the business after just one

meeting. The agency it beat was WPP’s Mindshare. I repeat, Mindshare. The reason, recalls, TMK Chief Digital Officer Darren Herman, “is they loved our ethos and our ideas for how we look

at the future.”

The reason for that, says TMK CEO Barry Lowenthal, is because of people like Darren Herman, who joined the agency in 2007 with zero

experience in either advertising or media services and has helped transform TMK into one of the most forward -thinking media organizations on Madison Avenue. That’s right, zero experience in the

ad business. That’s often the prerequisite job description for important jobs at TMK. In the case of Herman, he was a digital native entrepreneur — one of the founders of IGA

(In-Game Advertising) who made a small fortune when it was sold, and only pursued a role in the advertising business when his dad suggested he had better find a day job to keep himself busy,

and as luck would have it, he had already made the acquaintance of Lowenthal while he was at IGA, and Lowenthal just so happened to be looking for a head of TMK’s then nascent digital

operations. So nascent, in fact, that the agency basically wasn’t buying any digital media. Five years later, TMK ended 2012 with about 60 percent of its billings coming from digital

media.

To some extent, that philosphy of staffing eclecticism was started by Lowenthal’s predecessor, Paul Woolmington (now at Naked), who

preferred recruiting people without any advertising or media experience, but who were creative thinkers with diverse backgrounds. You can still see remnants of Woolmington’s original culture

hanging overhead in the Kitchen’s offices in Lower Manhattan — actual pots and pans connoting that it literally is a kitchen for cooking up big ideas. And the staff still call themselves

“chefs,” but Lowenthal has broadened the composition and the focus of the team to think more broadly about media.

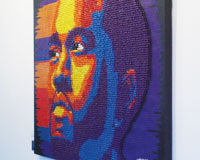

In fact, if you walk

through the offices of TMK’s sister agency, creative shop KBS&P, you might spot a portrait of Kanye West hanging on a wall. The portrait, which was created entirely with colored pushpins,

was created by Andre Woolery, digital synthesis director by day at TMK, but an up-and-coming fine artist by night.

If you ask Lowenthal, it is the sum of the

people, not the organizational plan, that define TMK’s culture and are what set it apart.

“When we were looking for a head of digital, the first person I thought

of was Darren,” recalls Lowenthal, adding, “He had never worked in advertising before and he’d never put together a media plan, but he was the most visionary person I knew, and he

got on the bus.”

In fact, Lowenthal says his whole approach to media services agency management comes directly from Jim Collins’ business management

book, From Good To Great, whose premise is that great companies “have the right people on the bus, and once they have the right people on the bus, then they figure out what to do. They

don’t figure out what to do, and then go out and hire the right people to do it,” says Lowenthal.

Which explains how the agency ended up with a

fine artist organizing its projects and operations, or with a serial digital entrepreneur as its Chief Digital Officer. In fact, it is Herman’s roots and passion for the digital startup culture

that are much of what differentiates TMK from other mainstream media shops today. Like many of the others, TMK has its own ventures unit. But unlike others, it has a disciplined approach that

doesn’t just look for startups that could be good early-stage opportunities for clients. KBS+P Ventures, founded by Herman, invests cash in promising startups in exchange for equity based on

expectations of financial, as well as intellectual capital returns. And he manages the unit like he would an independent VC fund with balance sheets reporting returns on equity.

The bonus for TMK is the early looks, strategic insights and ground floor opportunities to shape technology-based startups that could influence the way the agency and its

clients use media. The fund’s portfolio includes promising startups such as Yieldbot, PlaceIQ, Adaptly, Kohort, and Awe.sm, and while the fund hasn’t yet “exited” from any of

those investments, it has grown its paper value based on options some of those startups have already had to sell.

TMK’s entrepreneurism has even

incubated businesses inside the organization, such as state-of-the-art agency trading desk Varick Media Management, which now operates as its own freestanding company, with a separate P&L, though

it is inextricably linked to TMK, which uses it to trade all of its “biddable” media.

And TMK doesn’t just put its money where its mouth

is. Sometimes it fuels innovation among startups for innovation’s sake. That’s why this past year TMK organized #TASC, or the Technology Advertising Startup Council, with three rival

agencies — 360i, Deep Focus, and Anthem Worldwide. The goal of #TASC, says Herman, is simply to help foster new technology based businesses that will benefit advertisers and agencies.

That culture of startup entrepreneurism frequently blurs inside TMK, which encourages — and pays for — its staff to take courses at New York’s General

Assembly in areas that may not be apparently linked to the agency’s services. Instead of studying media planning, a TMK planner might take a course in how to write computer code. Others might

take courses in how to raise money from venture funds.

“The kinds of things our people study there aren’t necessarily going to make them better media planners,

but they are going to make them better people in general,” says Lowenthal, adding, “I want people who are interested in where they are going. I want people who want to be the next Mark

Zuckerberg. In the meantime, while they’re trying to figure that out, they have a great job in digital media.”

If that seems almost a little too

altruistic for an agency boss, consider this. When Lowenthal was recently introduced to a startup that developed a technology for training dogs not to bark when their families were away from home,

Lowenthal said the account was too small for TMK to take on, but he liked the idea so much that he encouraged some of his staff to work on it on their own time, and several became part of the

startup’s team while working at TMK as their day jobs.

Not many agency bosses would be that self-assured, but Lowenthal has the proof that it works,

and instead of losing people, the culture ends up retaining them longer than they might otherwise have. Herman is a good example. When he joined TMK, his goal was to stay two years. He’s

entering his sixth.

Part of what attracts and keeps people is that boundaryless sense of open opportunity created by TMK’s ethos. Herman points to

examples like the fact that every presentation the agency has ever produced is published for the world to see on Slideshare. The only time the agency removes presentations is when it “runs out

of space” and has to make room for new ones. Since 2009, when the agency started using Slideshare, it has published more than 300 presentations on the Web-based open access platform.

“A lot of other agencies like to hide their intellectual property,” says Herman, “because they think they’re protecting it. But innovation is all

about being open. Innovation doesn’t keep up when you lock it up in a room.”

It was that kind of spirit of openness and innovation, ironically,

that won TMK the account for Goldman Sachs, which some might perceive as a client that would be especially guarded, and has been struggling to rebuild its reputation due to its role in the 2007

financial services industry meltdown.

TMK’s solution was for Goldman Sachs to be open about the progress it has been making and to distribute that

story in as many places as it possibly could, just not on its own Web site. Instead, it partnered with a series of prestigious publishers including The Atlantic to create content tied to

Goldman Sachs’ story across the Web.

“The strategy was about not driving traffic to the Goldman site, which took them a little getting used

to,” Herman recalls.

Herman describes that approach “as high touch” and divides the work TMK does into two camps: High touch and biddable

media. Both are informed by TMK’s approach to strategic planning and communications objectives, but execute differently. The high touch approaches require lots of creative thinking and hands-on

execution from lots of people. The biddable media approach is just the opposite, taking an underlying media strategy, connecting it to powerful analytics, and letting it effectively run

itself.

Well, it doesn’t actually run itself. The biddable media executions either run through sister agency trading desk Varick Media Management, or

through KBS+P’s search group, but they are directed and overseen by TMK. Biddable media has become such an integral part of TMK’s mix that the agency has even created a new post, dubbed

the “biddable media engineer” to work between the account, strategy, and planning groups and the trading desk and search groups.