There are so few fairy tales left in business culture and lore in recent years. Jobs coming back to turn around Apple, Zuckerberg crashing the Harvard servers with the protean version of Facebook on

its first night, Bill Gates sniffing dismissively at company after company that would prove to get the drop on Microsoft. As digital media settles into maturity, there is also an ebb of glamor.

There are so few fairy tales left in business culture and lore in recent years. Jobs coming back to turn around Apple, Zuckerberg crashing the Harvard servers with the protean version of Facebook on

its first night, Bill Gates sniffing dismissively at company after company that would prove to get the drop on Microsoft. As digital media settles into maturity, there is also an ebb of glamor.

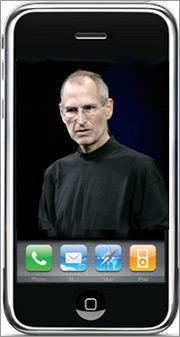

Which is why Fred Vogelstein’s upcoming book "Dogfight: How Apple and Google Went to War and Started a Revolution" seems delicious even in the excerpt published this week at Atlantic.com. It concerns the unveiling of the

iPhone in 2007 and how Google reacted. “We knew that Apple was going to announce a phone,” recalled early Android exec Ethan Beard. “Everyone knew that. We just didn’t think it

would be that good.” It is a great remembrance, but I wish I knew where Beard put his emphasis -- on "that" or "good."

advertisement

advertisement

It makes a difference because part of the fun of this tale is

how much the unveiling of the iPhone completely redirected the work that Andy Rubin and co. at Google were already doing on their phone design. The earlier iteration was called Soonr, and it looked a

lot like a jacked-up BlackBerry in physical design.

According to Vogelstein, Andy Rubin was watching the Jobs keynote in a car on his way to meet phone hardware and carrier execs. “Rubin

was so astonished by what Jobs was unveiling that on his way to a meeting, he had his driver pull over so that he could finish watching the webcast. ‘Holy crap,’ he said to one of his

colleagues in the car. ‘I guess we’re not going to ship that phone.’

Until then, Microsoft was seen by Google as the bigger threat when it came to phones. They had experience

and could be massively powerful if they succeeded in leveraging the Windows OS across screens. At least according to this history, Google wasn’t even on the same path as Apple until the iPhone

made them rethink both the OS and the hardware. It delayed Android a year. And it gave us two similar operating systems that would at least help coalesce what had been a hopelessly fragmented mobile

platform where "porting" alone proved cost-prohibitive for most developers.

Although he only spends a few paragraphs setting up the historical context in this piece, Vogelstein does a good job

of recalling just how unfriendly the mobile economy was toward content and marketing under a regime led by hardware OEMs and carriers. I know. I was there. As I watched, reviewed and chronicled the

waves of early apps, MVNOs, content carriage deals, “portals” and struggles over getting onto the phone “deck,” I wrote the same lament again and again. “Is this industry

really ready to be a media platform?”

It is still astonishing to me just how quickly that has changed so fundamentally. Like most business fairy tales, like most American myths, we like

envisioning the rise of the smartphone as a single innovation or insight powered by a visionary that changes everything. It is never entirely true, but the narrative fuels our mythology of

individualism and enduring faith in the transformative power of human agency. And yet in this case, the fairy tale -- perhaps one of the last ones of the early digital age -- seems closer than usual

to being reality.