Twenty years ago this morning, I was on a commuter train heading to my job in Rockefeller Center when the conductor announced “a plane” had struck one of the Twin Towers, and

for the rest of that morning I got to experience the 9/11 attacks vicariously through media.

I was on Metro North’s New Haven line, and the last time I got to see the Twin Towers was

when we passed over the Park Avenue bridge looking south at the smoke billowing from it. Then we dived into an underground tunnel when the conductor announced that a second plane had crashed into the

other tower and we all realized we were under attack.

But unlike today, when you can literally watch those kinds of events unfold live in the palm of your hand, this was before smartphones,

and the only updates we got were from someone listening to a transistor radio, or speaking with someone on their cell phone.

“I bet it was Osama Bin Laden,” my mother,

who lived in Lower Manhattan, said when I finally reached her.

advertisement

advertisement

“What’s Osama Bin Laden?” I asked, feeling incredibly disconnected and ignorant when she explained it

to me.

By the time our train pulled into Grand Central Terminal, we all knew the situation was bad, and the conductor announced that the train we were on was going to turn around and

head back out of the city for anyone who wanted to leave. Amazingly, most of the commuters got off, but as soon as they did, the train was flooded with others leaving the city.

The

ride north under the Park Avenue tunnel was one of the longest in my life, and when we pulled onto the 125th Street platform there was no room for the crowd of people looking to get on.

It now seems hard to imagine from today’s always-on, ever-connected media environment, but I didn’t actually get to see any images of what was going on until I got back to

Connecticut, drove to my home and turned on the TV.

Since most of the local stations had their transmitters located on the World Trade Center, we had to rely on coverage from those

that had back-ups on the Empire State Building.

By then, the cell phone circuits in Lower Manhattan were also knocked out, but I got an email from my friend Richard Morgan, who

resided in the shadow of the Twin Towers, and he asked me to call his parents in California to let them know he was okay.

It was the last event of that magnitude to play out in my

mind via snippets of analog media, and I as I searched in vain to find an image to illustrate this column, I realized how perishable they actually were.

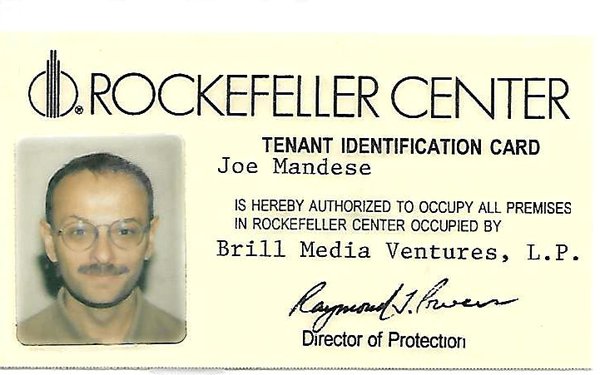

The best I could come up with was my

Rockefeller Center building pass (see below), which gave me access to the offices of Brill Media, where I was working at the time.

In the days that followed, our building’s mail system

was one of the distribution points for a series of anthrax mailing attacks that still have not been resolved, but which compounded the anxiety all Americans -- especially those living and working in

New York City -- were experiencing.

And from my vantage point in the media capital of the world, I realized that media was very much part of the experience, because it was the

ammunition that fueled the attacks to global proportions.

Twenty years later, I am grateful to the media industry for the responsible way it has replayed those events, especially

many of the specials that have been airing this week.

Because as much as media plays a role in amplifying acts of terrorism, it also helps us remember what’s important to us,

including the memories of those we lost or all who suffered from those attacks.

In some ways, we are all victims of 9/11, and I was struck by a story I wrote last week based on new

research from Ipsos showing how indelible a mark 9/11 left on America, including those who weren’t even born or were too young to remember it.