Forty years after I began covering

the advertising marketplace, I’m still scratching my head about the power and persistence of its culture, and how it preserves the mutual interdependence of buyers and sellers.

The first time I scratched my head was when I was preparing to cover my first upfront advertising marketplace 40 years ago and the head of sales of one of the Big 3 networks was generous

enough to brief me on how it worked, especially the fact that the networks required agencies and advertisers to register their ad budgets before they began negotiating.

When I asked

why they would do that in a supply-and-demand marketplace, he said it was so the networks could allocate their supply to them.

Forty years alter, I’ll be asking them once again

why they still do that at Thursday’s MediaPost Outfront Forum.

advertisement

advertisement

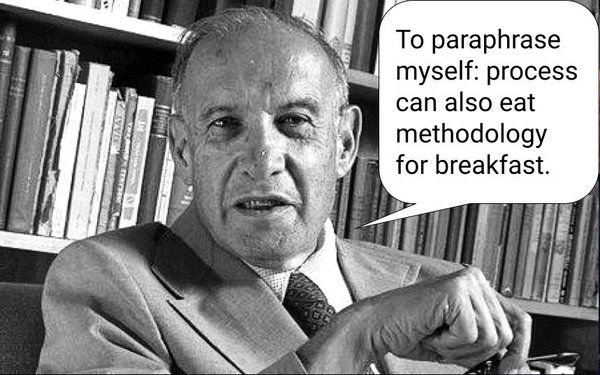

Of course, by now, I know the true answer and

it’s the same one legendary management consultant Peter Drucker used to explain the inertial dysfunction of any company or industry that operates against its own strategic interests: culture (as

in his famous quip: “Culture eats strategy for breakfast”).

The reason I still scratch my head isn’t because I don’t understand that. It’s because I

don’t understand why.

I mean, I definitely get that advertising still is a relationship business, and that buyers and sellers often are friends, help each other out with deals,

and even their own careers, or sometimes the careers of their children, etc., but I think the real reason is an even bigger factor, which is that people in any industry are averse to complexity.

And as convoluted as the upfront process might seem, it was built to minimize complexity. Sure there’s a couple of months of posturing and haggling, but once they reach a strike

price, the floodgates open up, billions of dollars of deals flow, and the rest of the process is based on simple legacy guarantees, “makegoods,” etc.

And I always find it

interesting when big industry honchos seem to have an epiphany that the process is illogical and needs to be fixed: whether it was David Verklin’s NUDG (Network Upfront Discussion Group) initiative two decades ago or Procter & Gamble’s Marc Pritchard "toilet paper" speech at this

year’s Association of National Advertisers’ (ANA) Media Conference.

And just like NUDG, I fully expect Pritchard’s rallying cry to succumb to the same thing that

ate Verklin’s initiative: the persistence of industry culture.

So I’ve spent a couple of months now kvetching in columns like this one about a variant of that: the

networks’ bum rush to eradicate the thoughtful, strategic approach to changing the industry’s “currency” – the audience metrics that are the basis of what advertisers

ultimately pay the media and measure their ROIs – in favor of a process-oriented approach that removes all that complexity in favor of finding a simpler way of actually processing all those

billions of dollars of ad spending.

If anything underscored that, it was last week’s Advertising Research Foundation #Audiencexsicence conference, which I quipped should have

been renamed #Audiencexprocess in a column entitled “Garbage In, Garbage Out.”

I got some pushback from the networks about using that headline, but after four decades of covering the thoughtful, methodological way the ad industry’s culture has at least tried to

preserve the integrity of its underlying currency – for better or worse – I believe it is toast. The kind that gets eaten during breakfast.

It was listening to Paramount

COO of Advertising Revenue John Halley’s explanation that it was time for the ad industry to move past “the methodologies” and focus on “operationalization” that nailed

it for me, and caused me to invoke data science’s GIGO standard, because if ever there was a case for that, it is moving from industry standard methods for currency to a Wild West approach of

“test and learn” of multiple alternative currencies certified not by any industry body, but by the people selling the stuff.

If there was one aspect of culture I did not

anticipate, it was how much parallel part of Madison Avenue’s – you know, its “digital culture” – had seized the day. I learned that from asking buy-side people at big

agencies why they were capitulating and letting their suppliers certify what metrics they can use as the currency

for doing business with them. Their explanation: That’s the way we do it with digital, and we no longer have the luxury of time to spend vetting and sanctifying new currencies the way we did in

the old days.

As part of that rhetoric, both buyers and sellers have told me they will ultimately be audited and accredited by the Media Rating Council (MRC), which still is the

industry’s neutral self-regulatory stamp of approval, but it’s interesting to note that only one of the new currencies – NBCUniversal’s iSpot – currently is even

undergoing the MRC’s process. And iSpot's audit only covers ad occurrence data, not audiences estimates, so technically, not one of the new currencies is even on track to be audited or

accredited.

I’ve been struck by other instances in which the industry’s culture eats its strategy, and have also found some of the pushback to some of the MRC’s own

standards – whether it was its original line in the sand for a minimum threshold of “viewable impressions,” or an even higher order one it established for “duration-weighted” ones – but I get that different cultures

sometimes persist on a variety of segments within an industry.

The good news is that even as those cultures persist, there are bodies like the MRC, and the ANA (Cross-Media Measurement Initiative) that remain focused on strategy, even if

they sometimes create friction for the rest of the industry.