One of the favorite sports of ad economy

watchers is trying to understand its relationship with the general economy. But there is mounting evidence that they have become completely untethered, at last in terms of the conventional ways those

comparisons have been drawn.

Take last week’s tech stock market tumble when Snap reported that “supply chain issues” had caused advertising to hold back on

spending, which in turn, contributed to Snap missing its third quarter earnings results. That, plus Snap’s other -- arguably more plausible explanation -- that Apple’s new iOS privacy

framework is doing to Snap what it’s done to Facebook and presumably other big data-dependent performance marketing platforms.

But as one of the best ad economy watchers --

GroupM Business Intelligence chief Brian Wieser -- noted this weekend, reports of supply chain constraints on ad spending have been greatly exaggerated.

“We still don’t

see much of an impact,” Wieser writes in this week’s GroupM “Global Marketing Monitor,” adding, “While there will undoubtedly be performance-based marketers who budget

for advertising with highly short-term-oriented objectives and who would reduce spending directly when they cannot drive immediate cause and effect, we are skeptical that these attributes are common

to the bulk of advertising.”

While concerns about supply chain constraints on the ad industry have been mounting all year, Wieser is among those who believe classic ways of

thinking about the correlations between advertising and overall economic activity may be outdated. For a variety of reasons.

“While the direct connection between advertising

and economic activity has been strained by degree during the pandemic, correlations are still high in many markets,” he writes, adding, “And for good reason: most marketers budget for

advertising with some relation to the percentage of revenues they generate, which means that growing revenues should mean growing advertising spending. Consequently, it’s hard to see

supply chain issues as having a meaningful impact on media owners, at least without more meaningful disruptions than have occurred to date.”

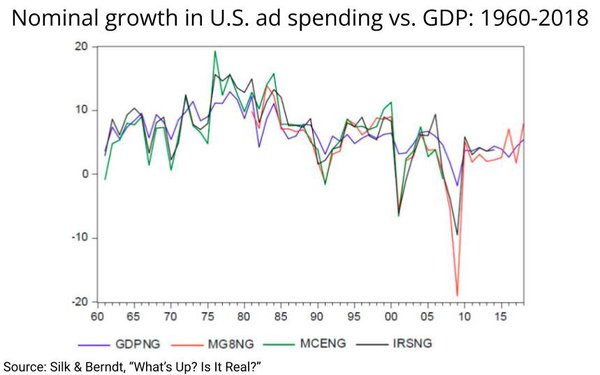

Wieser’s observation reminded

me of a working paper Harvard Professor Alvin Silk began circulating late last year that also makes the case that the relationship between advertising supply and demand and classic economic growth

measures are out of whack.

The paper, “Aggregate Advertising Expenditure In The U.S. Economy:

What’s Up? Is It Real?,” was co-written by MIT Professor Ernie Berndt, and is dedicated to the memory of Madison Avenue’s seminal economist, the late Interpublic forecaster Bob

Coen, who for decades correlated the relationship between advertising and the economy.

But the paper argues that a number of things have changed, including that classic macro

indicators such as gross domestic product (GDP) likely need to be rethought and that new “media-specific” indices need to be developed in its place in order to understand the true

relationship between advertising and economic growth. And vice versa.

There is further economic evidence to support Silk’s and Berndt’s these that there has been a

“structural break” in linear comparisons between the advertising and general economies.

For one thing, the very definition of advertising -- something Coen worked on

early in his career -- probably needs updating, because much of the ad budget spending that previously went into things that are easily accounted for, is now being diverted into things that may defy

categorization, or simply may not have been properly categorized. “Influencer marketing” comes to mind, as does “native” formats that may not be easily identifiable and

accounted for as actual advertising buys.

And as we enter new phases of media, technology and human interaction there are no experiences on the horizon -- things ranging from IoT to

NFTs -- that may exacerbate this definition by new magnitudes.

As I previewed this paper, I was thinking back to one of my favorite stories I ever covered, a project that Wieser took

on, and invited me to tag along on, right after he succeeded Bob Coen as then head of Interpublic’s forecasting. Wieser called it the “Social Sojourn,” and it was a one-day, rapid-fire taxi cab trip around New

York City events, experts and sources to help Wieser come up with a definition for social media: is it advertising or is it not?

As I tailed Wieser that day, May 18, 2009,

live-blogging dispatches of his meetings and insights via my Blackberry, I got to see the inner workings of Wieser’s mind, as well as those of the others he was tapping into. The event

culminated in Wieser’s conclusion that social media was not actually advertising and while an eye should be kept on it, it should not be factored into Madison Avenue’s official bean

counting. At least not yet.

Obviously, a lot has changed since then, and social media is very much a part of Madison Avenue’s official bean counting, especially now that

digital media in aggregate has become the lion’s share of overall ad spending.

But for all the scrutinizing Madison Avenue economists focus on social media, it’s still

probably not being properly accounted for. And once again, we have Wieser to thank for that insight. Over the past few years, Wieser has dug deep and identified “billions of dollars” in unaccounted for ad spending coming from Chinese

companies marketing to Americans, and people in other markets, via Facebook (as well as Google, Amazon and others).

The bottom line, as they say, is that Madison Avenue’s has

become a moving target and is sorely in need of an overhaul when it comes to comparing overall economic growth to it.