As a publication primarily concerned with the marketing

of pharma and health-related products and services, we tend to highlight campaigns that benefit consumers, doctors and society.

This week, though, we’ll enter the dark side due to two

timely reports that recently crossed our desks: one titled “UnTargeting Kids: Protecting Children from Harmful

Firearm Marketing,” the other “Bad Marketing: Litigation, Competition, and the Marketing of Prescription

Opioids.”

Thanks to entities like Northwell Health, we know

that guns are now the number-one cause of death among children. So shame on firearm companies who target kids, even if the practice isn’t explicitly against the law, as is the marketing of

tobacco and alcohol to minors.

advertisement

advertisement

The “UnTargeting Kids” study comes from Sandy Hook Promise, a nonprofit led by several family members whose loved ones were among the 26 people

killed in the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in 2012.

Partly drawn from materials unearthed during the successful lawsuit brought by the families impacted by the Sandy Hook

tragedy against Remington Arms, manufacturer of the AR-15-style weapon used by the shooter, “UnTargeting Kids” runs down a litany of practices used by firearms industry to reach kids.

This may be of particular concern right now, a week after the Lewiston, Maine, mass killings, as the report states that such events lead to heightened emotions and fears that new gun restrictions

could be passed. Firearm companies then step up their marketing to suggest that policy changes could come to reduce gun availability.

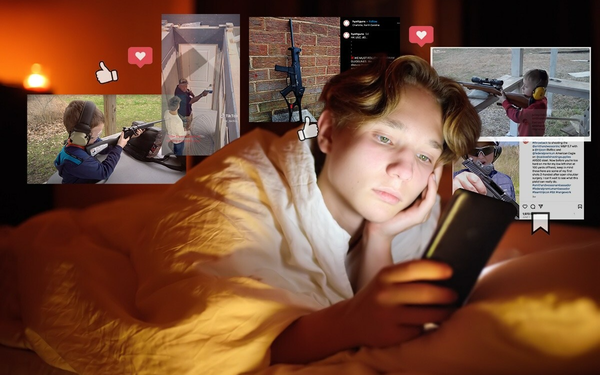

Marketing tactics that reach kids, the report says,

include increased advertising of “deadly military-style, semi-automatic firearms with R-rated psychological messaging about sex, power, and masculinity, to which at-risk youth are particularly

susceptible.” This is done through “traditional channels, such as magazines aimed at kids, as well as via modern marketing techniques, such as social media influencers, and third-party

advertising exchanges, which allow companies to sell ad inventory through a virtual marketplace.”

The report then zeroes in on how firearm manufacturers reach kids through TV, movies and

videogames, YouTube videos, social media influencers, and more.

“This is not a partisan issue,” Sandy Hook Promise concludes. “Gun owners and non-gun owners alike can agree

that kids should not be the targets of firearm marketing, especially content… that should only be viewed by adults.”

And everyone should be able to agree that pharma

companies’ aggressive marketing of opioids to healthcare providers (HCPs) helped lead to the ongoing opioid crisis.

This was on our mind with last week’s Netflix premiere of

“Pain Hustlers,” a fictionalized account of how Insys Therapeutics’ over-selling of its fentanyl opioid spray Subsys a decade ago helped lead to racketeering convictions for its key

executives.

Insys doesn’t enter into the new study of opioid marketing to doctors, published by the University of Washington’s Foster School of Business in Strategic Management

Journal.

Nor, surprisingly, is it an indictment of Purdue Pharma.

Instead, the authors go after Purdue’s opioid competitors, unnamed in the report, in the period following

the start of legal proceedings against the OxyContin manufacturer.

In 2014 and 2015, prior to those proceedings, the report finds that Purdue’s sales representatives spent $1.5 million

on food and beverages during HCP visits. That number dropped to only $54,000, a 94% decrease, in the years after the lawsuit, 2016 and 2017. But in the same period, competing companies’ sales

reps increased their spending by 160% -- from $911,000 to $2.4 million -- “despite increased stigma around prescription opioids.”

“The increase in competitor promotional

spending was targeted very specifically at prescribers of the OxyContin brand of oxycodone and at prescribers previously targeted by Purdue’s promotion of OxyContin,” says co-author and

associate professor of management David Tan.

“We hope that when one company gets sanctioned, other companies will take that as a warning and try to avoid those kinds of activities.

The ideal is that private lawsuits against individual companies have the potential to bring about industrywide change,” Tan continues.

“Unfortunately, I think, rather than serve as

a warning to the rest of the industry, this lawsuit created an opportunity for competitors by weakening Purdue’s marketing grasp over its lucrative OxyContin prescribers.”

On a

more positive note, Tan says that since 2017, local governments across the country have filed thousands of opioid-related lawsuits, “leading several firms — Purdue Pharma included —

to file for bankruptcy.”

“That has served as a much more severe warning against the prescription opioid industry and encompasses a wide range of behavior,” he concludes.

“Our study covers direct-to-physician promotion, but these lawsuits also extend to other undocumented forms of promotion…such as allegedly funding nonprofit front organizations to

influence prescribers’ beliefs about opioids… The weight of these settlements has at least tempered behavior on the part of prescription opioid firms.”