The data says few people

trust AI. At least not in the U.S. But do we trust these data?

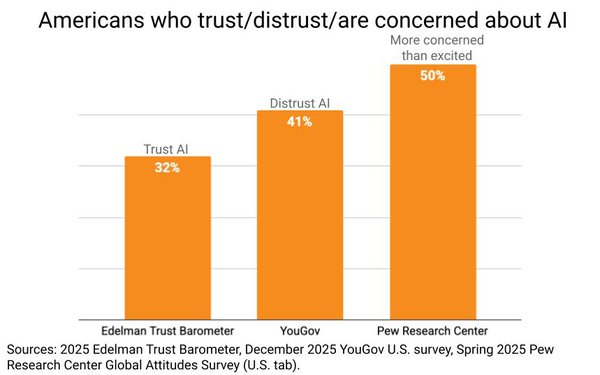

The 2025 Edelman Trust Barometer finds just 32% of American respondents trust AI.

In a December 2025 U.S.

YouGov survey, 41% said they distrust AI.

U.S. results from the 2025 Pew Global Attitudes survey found half are more concerned than excited about AI, and taking account of the full range of

sentiment, the U.S. has the lowest regard for AI worldwide.

There are a lot of theories floating around about why trust in AI in the U.S, is so low.

One theory is that

it’s a consequence of declining trust in Big Tech.

A similar theory is that it’s due to our collective negative experience with social media.

Another theory says it’s

because nobody trusts government to regulate AI for the better instead of neglecting it for the worse.

advertisement

advertisement

Yet another theory says it’s because people are worried that AI will upend their

lives by taking their jobs and compromising their privacy.

But what are these data really measuring? Is it mistrust of AI or ignorance of AI? Mushiness theory would say that it is

too soon to know, but probably ignorance. Pundits and marketing strategists have declared that AI has a trust problem. But what the data reveal may well be nothing but the usual corollary of

unfamiliarity.

Mushiness is a concept developed in the early 1980s by pollster and social theorist Daniel Yankelovich. At that time, Dan’s namesake firm conducted the

Time magazine public opinion poll. To accompany these polls, Dan wanted a metric to better calibrate results and to improve how results were reported and used. So, he developed an index that

he called mushiness to gauge how firmly people hold the opinions they express in a survey. (Ultimately, Time opted not to use this index, but that’s a story for another day unrelated to

the validity of the index itself.)

Dan had a low regard for run-of-the-mill opinion polls. He thought that the typical poll was superficial and shallow and thus dangerously

misleading, particularly for things like foreign affairs and fiscal budgets for which politicians turn to public opinion for feedback about priorities and policies.

Dan’s root

concern was that survey respondents answer whatever they’re asked, even when they have no prior opinion about a topic or any knowledge of it. It’s worse these days with pre-recruited

panels because respondents get paid only if they answer. From Dan’s perspective, what this means is that all too often survey results report artificial opinions not real opinions.

Real opinions are what drive decisions, at least in Dan’s view. When people are faced with an actual choice, as opposed to a survey question, they will firm up what they think by

gathering more information and discussing things with other people. In other words, they will make themselves more knowledgeable. Thus, survey opinions are mushy -- they are uninformed and

haven’t firmed up into the real opinions that will ultimately shape decision-making.

One critique of Dan’s notion, of course, is that many decisions are habitual or

emotional, having little to do with being informed or knowledgeable about a choice like a product or a brand. But Dan never argued that only "correctly" informed opinions were firm opinions. Instead,

it is a matter of whether people feel informed or knowledgeable, which was part of the genius of the mushiness index. Because it turns out that people will honestly tell you if they know about a

topic, so that was a component of the index.

The other component is whether people feel any personal relevance to the topic at hand. If something is arms-length away, the answers

people give in a survey will reflect the fact that people have nothing invested in the answer. If something becomes relevant later, perhaps because people learn more and realize it does affect them,

then people’s opinions will firm up. Until then, survey opinions are mushy.

So, what does mushiness have to do with trust in AI? Well, it turns out that familiarity with AI is

a big factor with respect to trust in AI. Kantar U.S. MONITOR data collected late last year find that the more people use AI, the more trust they have in AI. Among frequent AI users, 86% are positive

about AI becoming a bigger part of people’s lives versus 44% of infrequent users. Similarly, 62% are open to an AI assistant doing all their routine shopping versus 24% of infrequent users.

This disparity of sentiment is true for everything: Worries about negative consequences. Making major purchases with AI. Even having AI as a boyfriend, girlfriend or regular friend.

Sixty-five percent of frequent AI users believe wellbeing recommendations from AI are just as trustworthy as advice from a human doctor, compared to 32% of infrequent users.

Now,

these group differences don’t settle the question raised about mistrust or ignorance. It’s still chicken-or-egg. Are frequent users the most positive to begin with or did they become more

positive as they became more frequent users? Nonetheless, there is a clear correlation of frequency and trust. Thus, at the very least, overarching pronouncements of mistrust in AI elide a critical

dynamic in the marketplace -- there is already a critical mass of people who trust AI, certainly enough people to build a robust commercial ecosystem.

These group differences,

however, do align with mushiness as a testable proposition, one that offers a different view of how to proceed with AI. Lack of trust would recommend policies to rein in AI in order to build

confidence in the technologies slowly but steadily. Mushiness, on the other hand, would recommend policies to accelerate exposure to and usage of AI so that people can acquire the experience and

knowledgeability that will lead inevitably to trust.

The history of past technology innovations suggests that we should take mushiness seriously -- and test it rigorously -- as the

explanation for what we see in the data. In every instance in the past, new technologies have encountered initial trepidation and pushback that eventually goes away. Pundits worried the telephone

would expose women to predators and that television would dumb us all down. Despite headlines, the hard science about social media and mental health remains unsettled. ATMs grew alongside growth, not

decline, in the number of bank tellers.

In every instance, our worries about technology have been premature and overblown, largely due to ignorance. As we learned to use

technologies, we figured out how to get the best from them, and how to control them to avoid the worst. We didn’t trust them at first. But as we become more knowledgeable, our opinions became

more informed and more firmed up for the better.