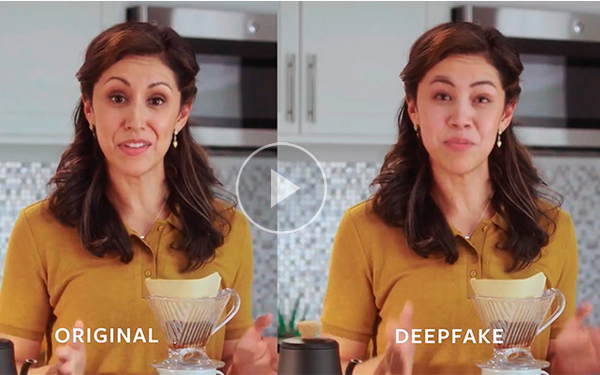

Facebook has announced that it is banning videos manipulated to

distort reality, commonly called “deepfakes.”

“While these videos are still rare on the internet,

they present a significant challenge for our industry and society as their use increases,” Facebook Vice President Global Policy Management Monika Bickert posted on the platform’s blog.

Bickert is

scheduled to testify this week before a House hearing on “manipulation and deception in the digital age.”

advertisement

advertisement

Going forward, Facebook will remove media that has been “edited or

synthesized, beyond adjustments for clarity or quality, in ways that aren’t apparent to an average person and would likely mislead someone into thinking that a subject of the video said words

that they did not actually say,” states the post. Content that is “the product of artificial intelligence or machine learning that merges, replaces or superimposes content onto a video,

making it appear to be authentic,” will also be banned, it states.

The policy doesn’t apply to parodies or satire.

Nor does it apply to video edited “solely to

omit or change the order of words” — although, if a Facebook fact checker rates a video as false or partly false, the platform will “significantly reduce its distribution in News

Feed and reject it if it’s being run as an ad,” says the post. Also, “people who see it, try to share it, or have already shared it, will see warnings alerting them that it’s

false.”

According to The Washington Post, the new policy appears to apply to the large number of deepfakes

created to harass women by superimposing their facial images on pornography.

However, despite manipulated videos’ implications for attempting to influence voters — as Russia did in

the 2016 election — the new policy does not appear to apply to political or other content that is not technically considered a “deepfake.”

That would appear to be the case

for one of the most well-known and controversial examples of manipulated media: the altered video of Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi that has been viewed more than 2.4 million times on Facebook

since its posting last May. When it went viral, Facebook acknowledged it to be false, but refused to delete it, saying its policies do not require that information posted on its platform must be

true.

“Though [Pelosi’s] speech was slowed and distorted in the video to make her sound drunk, the effect was accomplished with relatively simple video-editing software,”

making it a “cheapfake” or “shallowfake,” as opposed to a “deepfake” that would fall under the new deletion rule, notes the Post.

“Nor does the

policy seem to restrain other simpler forms of video deception, such as mislabeling footage, splicing dialogue or taking quotes out of context, as in a video last week in which a long response Joe

Biden delivered to an audience in New Hampshire was heavily trimmed to make him sound racist.”

Since these and

many other “cheapfake” videos are as misleading as ones produced through more sophisticated techniques, Facebook should be addressing the real issue—the misleading nature of some

content — rather than focusing on the nature of the technology, digital forensics expert Hany Farid asserted to the Post.