A Wall Street Journal story

on Tuesday reported that casual cursing as part of the normal discourse between people has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, but regular TV watchers know that profanity has been increasing on

the tube for years.

It sometimes feels a little too convenient to blame (or credit) various changes in society and behavior on the pandemic, as if some societal

trends were not already in full swing long before COVID.

This is not to say that the pandemic, which entered

all of our lives in March 2020, has not been an agent of massive change.

In addition, the research about cursing that is cited in the Journal is by

all appearances legitimate, with some possible caveats.

advertisement

advertisement

For example, says the paper, a study by Storyful from the full year of 2019 through November 2021

found that cursing rose 41% on Facebook and 27% on Twitter.

Of course, the full year of 2019 came before the pandemic changed our lives.

But

the WSJ story contains additional research and anecdotal evidence that support Storyful’s conclusion about an increase in casual cursing throughout the land -- both privately and in

business settings.

In one of the story’s best quotes, a Boston executive offers the opinion that the “relaxing of language” (the story’s

words) is related to “a parallel relaxation of how we dress now.” Profanity “is the yoga pants and Uggs of language,” the executive is quoted as saying.

However, anyone who lives in the world and is reasonably observant and alert knows that f-words and other examples of words that once upon a time were taboo (or at least

frowned upon) are overheard now everywhere you go.

If these kinds of words were used in the past in conversations between ordinary people, then it was also

true that they were not used in mass media such as newspapers, magazines, movies, radio and television.

TV in particular maintained a chaste approach to

language for at least its first three decades for two reasons -- audiences would be offended and, more importantly, advertisers would not buy commercial schedules in such an environment.

Both of those reasons have been in reverse for at least two decades. Today, audiences are not offended and advertisers place their commercials in all sorts of TV

environments that previously were off limits.

Profanity -- mainly the unnecessary, gratuitous variety that adds nothing to a show’s plot or character

development -- is a subject that the TV Blog has brought up from time to time.

The coverage here, and even previously at other media outlets going

back a decade or more, long predated the pandemic. The first one here goes back to 2014.

In another one published here in September 2017, the lead sentence

declared: “It is time for the TV Blog to close the book on the subject of the f-word.”

It just seemed at the time (as it has at

other times) that the battle for good taste (you might say) in the words used on television was essentially a lost cause.

“As with most content-related

subjects a critic harps on, the harping is all for naught,” I wrote then.

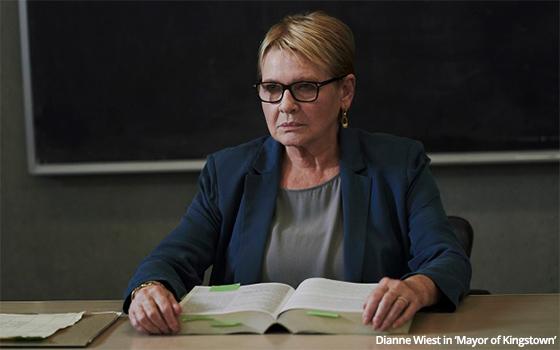

Predictably, this declaration did not hold. Just last month, the topic came

up again in a review of “Mayor of Kingstown,” the new gritty drama on Paramount+ in which the f-word is heard more often than any other word in the English language, or so it

seemed.

This even included a character played by Dianne Wiest (photo above), who is not exactly known as a female Joe Pesci.

The prevalence of f-words and other profanity on TV serves as pretty strong evidence that society’s resort

to casual cursing has been a fact of our lives for a lot longer than the pandemic.

This is because TV is often a reflective medium, in that it does not

necessarily jump-start social trends (although some might debate this). Instead, it is more likely to follow them or run parallel to them.

At some point

going back 20 years or so, the creators and presenters of TV content evidently began to come to the conclusion that increasing the curse count on their shows would probably be OK with viewing

audiences who were already way ahead of them. And they were right.