Spoiler alert:

Today’s column is another one in which I grouse about some personal consumer experiences in order to make a point. If you consider those self-indulgent, please do not read this one.

This column began in late December when I purchased an expensive piece of exercise equipment from a regional sporting goods retailer named Dick’s. It ends nearly four months later with

the company’s customer relations team refunding my purchase and sending me a $150 “appeasement.”

Now $150 may seem like a lot of money for months of aggravation,

but it was actually about the amount of interest I would have gained if I had invested my money instead of having it held hostage by a retail brand.

The story is more than the tale

of a frustrated consumer experience. It’s about the dysfunctional nature between a modern retailer’s ecommerce and store experiences, how they have been exacerbated by “supply

chain” and logistics issues -- but mostly about the worst thing any brand can do when something goes awry with its brand experience: Its failure to communicate clearly in a way that would manage

the consumer’s expectations, regardless of how it got resolved.

advertisement

advertisement

I’ll spare you the gory details, but the Cliff Notes version is that I tried purchasing the product from

the retailer, not once, but twice, when my local store manager refused to give me my pick-up order, requiring me to reorder it for delivery from another store much father away, which could not fulfill

that order, because it couldn’t source truck drivers to deliver it.

After months of calls and emails with multiple Dick’s customer support staff, it finally became clear

that I would never actually receive the equipment, so I finally canceled the order, leading to my refund and the $150 “appeasement” -- a word I had never heard used by a brand in more than

half a century as an American consumer.

“If you want to repurchase the item, I’ll help you do that,” the Dicks customer relations manager offered after the order

was canceled.

I thanked her, but said that two tries and four months was enough for me and that I had no confidence that another try would be any better.

What’s the main point of this personal consumer anecdote? It’s that I used to think the worst thing any brand could do to a consumer -- aside from ripping them off -- was to

waste their time. And while that’s a cardinal sin committed by many brands, it’s actually not the worst offense.

The worst thing a brand can do to a valued consumer

is to hold them hostage. To literally dick them around. To pointlessly and unnecessarily stretch out an unsatisfactory consumer experience that I coined a new consumer marketing term to

describe.

I call it the Consumer Stockholm Syndrome, because sometimes these experiences depend on the consumer becoming complicit and empathizing with their brand captors.

And over the months I was getting dicked around by the sports retailer, I thought about how many other Stockholm experiences I was suffering from. Interestingly, many of the worst offenders

are media brands -- especially my broadband provider and some of the streaming services I subscribe to whose business models depend on the concept of consumer “churn.” They literally

operate on an assumption that they will make your relationship so untenable that at some point it will become unbearable enough for you to free yourself from your bonds, jump back into the abyss of

another competing brand, and try your luck with them.

That’s definitely been the case with my broadband provider, Altice’s Optimum, which until this month was the

monopoly provider in my area. Over the years, I had already cut out my TV and telecommunications services, opting instead for a vMVPD provider for TV (YouTube TV) and my mobile carrier for household

calls.

I had been praying for my wireless carrier to begin offering a 5G household router so I could cut the Optimum’s cord altogether, but a competing broadband provider

has entered my neighborhood, so I’ll give them a try.

Broadband providers may be the most extreme example of consumers being held hostage by brands, because they are

often actual monopolies, but the Optimum story gets even more twisted than that and rises to the level of a Stockholm experience, because it never actually let me cut my TV and phone package.

Instead of letting my remove them, it has continued to offer me a so-called “Triple Play” bundled package that was cheaper than paying for a broadband connection alone. The trick

is that I had to call them back each year and ask them to renew it, in which case they would try and talk me out of it and upsell me to other services like their own wireless phone package (as

if).

I’ve repeated this process for several years now, and each year there’s a lapse in the renewal offer that pushes my monthly rate up for a month or two, so that

Optimum is making a profit on that churn.

This year I asked them why they were charging me a higher rate for another month even though I called them prior to the anniversary date

they asked me to check back on. “That’s because it takes us a month to process the new order,” the customer service representative explained.

“You literally

market yourself as a high-speed communications provider, and you’re telling me it takes you a month to update your own records,” I replied?

Thanks to getting dicked

around by a retail brand, I was also inspired to say enough is enough with Altice’s Optimum, so I’m canceling that service and switching to another, if for no better reason than I

don’t want to be held hostage by my brands.

Whether it is a service provider operating on the assumption of consumer churn, or a retailer grousing about “supply

chain” or logistics issues, there is one thing all brands can do to avoid this kind of experience. Simply communicate honestly and openly about what’s going on, and let the consumer decide

if it’s worth being your customer.

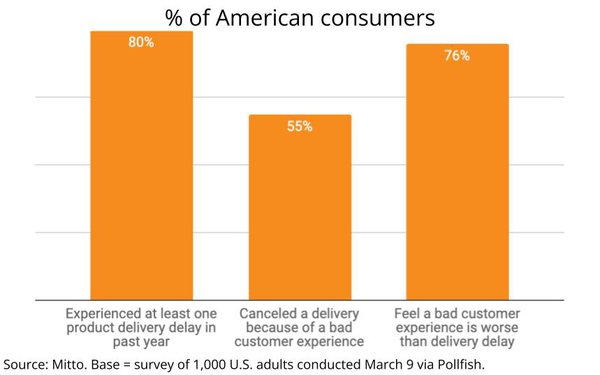

I know I'm not alone, because I have some hard data to prove it: some new American consumer research being released this week by customer

communications platform Mitto.

The study found, not surprisingly, that delivery delays have become the norm (80% of Americans have experienced at least one in the past year), but it also

affirmed that it's not just the delay, but the negative experiences associated with it that have caused consumers to 1) cancel their order (55%); or 2) feel worse than the experience of actually being

delayed (76%).

The findings also point to a relatively simple solution for avoiding these pitfalls, and it all comes down to clear, proactive communications to update consumer expectations

(see below). I mean, is that asking too much?

If you go to Dick's about page, it tells a pretty folksy story about a family-run

retail operation founded by Dick Stack in 1948. It features a vintage photo of two men holding fishing rods in the store's tackle areas, and presumably one of them is Dick.

I find the photo an

ironic metaphor, and I'm just glad I can say I can be included among the ones that got away.