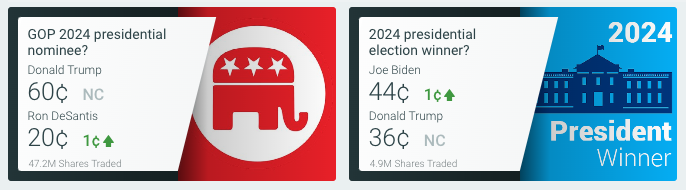

The above

picture includes prediction market trading from the PredictIt prediction market as of July 18, 2023.

Prediction markets are virtual markets designed and conducted to

forecast future events. They differ from typical markets in that their purpose is to provide forecasts rather than a means with which to buy and sell products such as stocks.

The way

prediction markets work is that people buy and sell shares based on how they think a candidate will do in an election or how a movie or TV show would do in the marketplace. The buying and selling

activity generate market prices that are highly predictive of what will happen.

advertisement

advertisement

Prediction markets rely on a research methodology based on a theory called the wisdom of crowds. This is

different from polls and sampling methods that rely on probability theory.

Whereas probability theory says that if you randomly choose a subset of people or sampling units, the information you

glean from them will be representative of a larger population.

The wisdom of crowds, on the other hand, says that if you total people's insights, the combined wisdom of the crowd will render

forecasts that are close to actual outcomes.

Although not widely used, the wisdom of crowds has been around a long time.

According to a book written by James Surowiecki

entitled The Wisdom of Crowds, the theory was developed in 1906 by an 85-year-old British scientist by the name of Francis Galton.

Galton was at a regional

fair where local farmers and townspeople gathered to appraise the quality of farm animals. This included placing wagers on the weight of an ox. The best guesses received prizes.

After the

contest was over, Galton asked for the tickets and ran statistical tests on the answers. There were 787 in total. However, he had to discard thirteen because they were illegible.

One of the

tests was to calculate the mean of the contestants' guesses. The average Galton calculated was 1,197 pounds. The actual number was 1,198 pounds. To Galton's great surprise, the wisdom of the crowd was

highly accurate.

Galton's intent was to prove that people's breeding would provide the best answers. What he learned was that democratic judgement was a lot better than expected.

Examples of modern-day uses of wisdom of crowds include the Iowa Electronic Market (IEM), the Hollywood Stock Exchange (HSX), PredictIt and Media Predict. These are all what are known as prediction

markets.

IEM and PredictIt predict outcomes of political elections, HSX predicts movie box-office results and Media Predict was created to forecast audience sizes for TV show concepts.

Most

prediction markets use play money. However, IEM is a real money market and Media Predict gives participants money to use so they cannot lose their own.

The fact that there is money on the line

that respondents can lose makes people more truthful in their assessments. In a poll or survey, there is not the same incentive for people to be honest.

According to a University of California Berkley Haas

Business School professor by the name of Don Moore, most election polls report a 95% confidence level.

Yet an analysis of 1,400 polls from 11 election cycles found that the

outcome lands within the poll's result just 60% of the time. And that's for polls just one week before an election — accuracy drops even more further out.

The confidence level is only a

gauge of sample error. It doesn't account for all the other types of error that can creep in while conducting polls and surveys.

In 2007, three researchers from the Henry B. Tippie College of

Business at the University of Iowa conducted a study called Prediction Market Accuracy in the Long Run to determine whether the IEM prediction market outperforms polls a long way in advance -- not

just on the eve of an election.

They aggregated over 965 polls over five Presidential elections and the IEM market was closer to the eventual outcome 74% of the time. Furthermore, the market

significantly outperformed the polls in every election when forecasting more than 100 days in advance.

There is also a lot of academic research done for HSX. In a study about HSX prediction

accuracy conducted by Benjamin Olsho at Pennsylvania State University, HSX had a Pearson Correlation Coefficient of 0.96 and a mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) of 23.

The Pearson

Correlation Coefficient measures the strength of the relationship between two variables, in this case the HSX prediction and the actual box-office revenue. A 1 is strongest and a 0 is least strong. A

0.96 score is very high.

The MAPE means that on average, the HSX prediction the prior day before the opening weekend of a film was within plus or minus 23 percent of the actual opening weekend

box office figure.

It's more difficult for any prediction methodology to forecast a precise number like box-office revenue or average audience size from more than 100 days in advance. HSX's

MAPE increases to 44% at 80 days before release.

When I was working there, the Media Predict prediction market produced a white paper based on its first year of operation. At that point, it

had generated 53 predictions for shows that averaged over 1M viewers. For eve-of-premiere predictions, MP averaged 85% predictive accuracy (+/- 15% of actual figures). Long-range accuracy was

similarly high even as far out as 70 days.>

From experience I can tell you that prediction markets are not a crystal ball. Perfect prediction is not available to us mere mortals.

They are, however, a powerful prediction tool for people looking to make decisions about donations to political campaigns and for investments related to film and TV show production.

Ignore

them at your own risk.