The first time I ever published the term "hybrid warfare" was in September 2017,

after Facebook revealed a Russian disinformation campaign spent $150,000 to buy about 3,000 ads on the social network to disrupt the 2016 presidential election.

It was the first time I heard

the term, but it is one that military and counter-intelligence experts use to describe a form of combat "blending

conventional warfare, irregular warfare, and the use of other capabilities such as cyber, disinformation, money, and corruption in order to achieve a political outcome."

According to

Facebook's post-election analysis (*), it had also begun to include social-media ad buys.

advertisement

advertisement

By now, even if you're not familiar with the explicit term "hybrid warfare," you probably know how

Russia's Internet Research Agency leveraged a minuscule ad budget to sow doubt and division in America that -- along with other "active measures" -- helped disrupt the outcome of the 2016

election.

MediaPost even awarded the Russian agency one of our Agency of the Year Awards based on the ingenious way it leveraged a tiny ad

buy, and social-media amplification, to achieve such a radical outcome.

But that's all in the past, right?

In today's post, I'd like to tell you about a new form of hybrid warfare I

recently learned about from the political media-buying experts at Stagwell's Assembly unit.

It's not a military one, as far as anyone knows, but a political-marketing one that has implications

for American politics, free elections, and even the advertising and media-buying marketplace -- especially local broadcast stations that depend on political media-buying cycles to remain vital.

"There are two types of political advertisers, candidates and independent expenditure groups," explains Assembly Director of Political Strategy Tyler Goldberg, adding that the independent

expenditure groups include political action committees (PACs), and a variety of other sources of political -- usually issues-oriented -- media buys that exploded over the past 15 years following the

Supreme Court's so-called "Citizens United" ruling, which effectively enabled corporations, as well as individual billionaires and

other entities with access to some less-than-well-lighted sources of money, to spend whatever they wanted on elections.

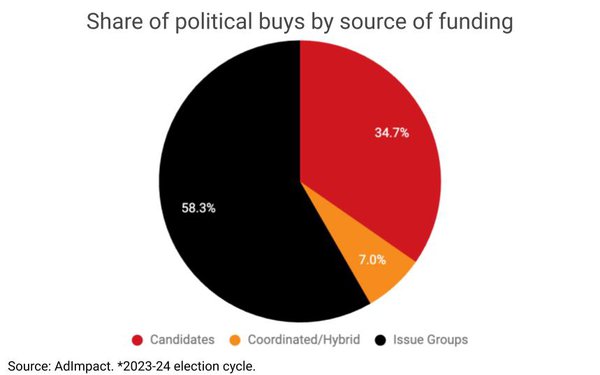

According to data political ad-tracking service AdImpact provided for

this column, issues-group spending has grown to nearly two-thirds of all advertising buys during the 2023-24 campaign cycle.

But if you look at the chart above, it's that new slice

representing 7% of all election ad spending that is what this column really is about -- a form of media buys in which some or nearly all of the money backing individual candidates is coming from the

issues groups, not the candidates themselves.

"What this is doing is taking advantage of a loophole in what are called hybrid ads," Assembly's Goldberg explains, noting: "These ads are funded

by the issues groups, but placed directly out of the candidate's campaign."

As Goldberg explains it, there are some nuances and disclaimers required for issues groups to directly back

candidates' advertising buys, but those lines are often blurry, likely in need of review by either or both of the Federal Election Commission and the Federal Communications Commission, especially

because of a loophole enabling the issues groups' massive media buys to qualify for the same lowest-unit rates that the candidates do.

Federal rules require broadcasters to give candidates the lowest ad rate paid during the 45-day period leading up

to a primary and 60 days leading up to a general or runoff election.

But according to Assembly's post-buy analysis of 2024 election spending -- and backed up by the AdImpact data provided to

"Red, White & Blog" -- the new loophole enabled issues groups to spend hundreds of millions of dollars on broadcast media buys that qualified for the lowest unit rates.

That's a concern

for two reasons, Goldberg says.

One is that the loophole was developed and used mostly by one side of the 2024 election cycle: Republicans.

The other is that it created a workaround

enabling the issues groups' media buys to qualify for broadcasters' lowest ad rates, thereby depriving American TV and radio stations of considerable political advertising margins.

Much of

that money ended up funding Republican, House and some gubernatorial races.

For example, Assembly's post-buy estimates that only about 2% Kari Lake's massive, multimillion campaign in the

Arizona governor's race came directly out of her campaign's advertising budget. Lake ultimately lost that race, but it was close. She currently is Donald Trump's nominee to run the Voice of

America.

"We've seen some of this before, but certainly not to the extent that we saw it in the last election cycle," Goldberg says, adding: "When we first saw it, we thought maybe these were

candidates struggling with fund-raising, but as the tactic expanded to all of these other Senate and House races, it became clear that it was a way for them to qualify for lowest unit rates."

While the federal lowest unit rate policy does not apply to digital media buys, Goldberg believes they should be, because digital is a rapidly growing part of the political media mix, and the

rates, as well as the public disclosures of ad spending transparency, were conceived in the spirit of the FEC's and FCC's pre-digital political campaign rules.

To be sure, Goldberg and others

alluded to the need for reform amid a rapidly shifting political media mix increasingly tapping digital, social, podcasts, as well as paid influencer buys, all of which are completely unregulated and

put broadcasters at a marketplace disadvantage.

"I may be a little idealistic about it, but it's something that needs to be addressed, because the problem is only going to get bigger,"

Goldberg predicts.

* Ironically, the link to the original report by former Facebook Chief

Security Officer Alex Stamos no longer works, but there are at least various news accounts summarizing it,

including this one by The New York Times.