During nearly half a century covering the advertising

marketplace, nothing has fascinated me more than the concept of "dark

media," which are the parts of the media universe that influence consumers, but are effectively invisible to ad industry practitioners.

But it wasn't until 2011 that I had a term for it.

That's when a now defunct company called Tynt began sharing some data with me showing that about 80% of the social media universe was effectively dark to the ad industry. And I've been trying to

benchmark how much of the rest of the media universe is also dark to the ad industry.

It's not just a theoretical exercise, because much of the foundational logic of advertising and marketing

-- especially return on ad spending (ROAS) -- is based in some form on shares of something: share of audience, share of voice, share of market, etc.

advertisement

advertisement

In other words, if you don't know what your

denominator actually is, what good is your numerator?

Over the years, I've done my own back-of-the-envelope analyses trying to determine which parts of the media marketplace are dark, and I've

concluded that nearly all of them are to some extent. You just need to step back and look at the whole.

My theory is that for all the science and research of advertising and marketing, most of

the media universe still is dark, because the vast majority of marketing spending actually is "below-the-line" -- and that's the part we actually try to measure. And when we do, like the recent

purported boom in "retail media," we put a name and a number around it and pretend that it's something new.

In the case of "retail media," it's something north of $100 billion and heading to

half a trillion fast. Or is it?

My contention is that the vast majority of retail-media spending has always existed, but we just had different names for it: promotion, FSIs, in-store media,

etc. And the only thing really new about it is that most of it is now digital.

But the same thing could be said of most media, and the more important part is that the spending was always

there. It was just called something else.

Anyway, this is an overly long set-up to today's Performance Marketing Insider column, which I'm filling in for regular columnist Laurie

Sullivan, who is off today.

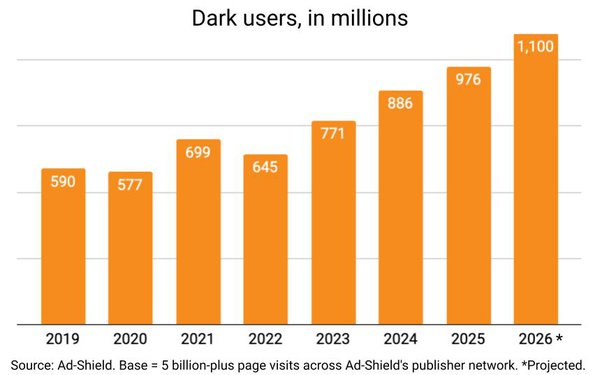

In preparation, Laurie shared some information about an important study being released this morning by anti-ad-blocking platform Ad-Shield, which has been studying

the phenomenon of "dark traffic." These are internet users who, because they willingly or unknowingly utilize ad blockers, are effectively invisible to advertisers -- or at least the ads they serve on

publishers' pages.

Laurie has been covering Ad-Shield's benchmarking for a couple of years now, but I only paid

it half a mind, because I was focused on other parts of the media universe until I read and dug into Ad-Shield's just-released report titled

"Adblocking: The Rise of Dark Traffic."

If you're interested in understanding the dark internet traffic

universe, I recommend you read it yourself, but the top lines should be of interest -- make that concern -- for anyone trying to reach consumers online, especially those trying to estimate the

performance of their attempts to do that.

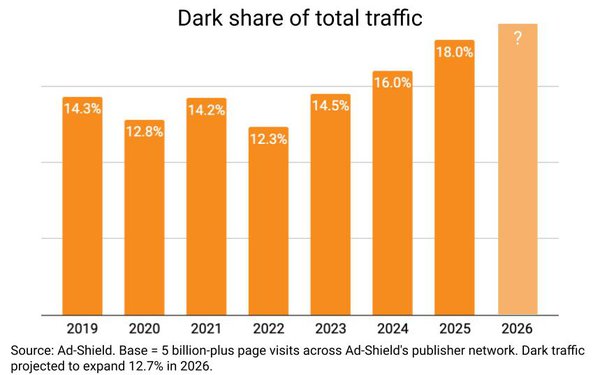

That's because Ad-Shield estimates that nearly a fifth (18%) of internet users are now dark to advertisers, and that percentage continues to grow (see

chart at bottom).

In the U.S., which is among the most-developed markets for ad blockers, 21% of internet users currently are dark.

The report goes into great detail about how and why

this is happening -- especially the emergence of a new class of ad blockers that Ad-Shield dubs "brutal," because consumers often aren't even aware they're blocking ads by using them, and have little

if any control over gating advertising, even if they did know.

There's also some interesting primary consumer research contained in the report addressing consumer knowledge and expectations,

which is worthy of its own column, if not a free-standing report too.

But I'll leave you with just two of those consumer insights:

- Most users (57%) never chose to block

advertisers in the first place.

- And perhaps most ironic of all, the No. 1 source for learning about the brutal ad blockers they eventually chose to use came from advertising

(among the 34% of study respondents who said they could remember the source).

On the bright side, that last stat goes to prove that advertising actually works -- when it gets through

to the users who see it.