Ad buys are a lot like lunch. There ain't no free

ones. Or in the case of the burgeoning CTV advertising marketplace, there are no cheap, high-volume ones either.

That was one of the big take takeaways from the CTV ad fraud panel that

closed out Tuesday's CIMM East conference in New York City. But if you ask me, there was an even bigger -- and far more controversial point -- made by a couple of the panelists, especially Simulmedia

CEO Dave Morgan.

Asked by moderator and CIMM Managing Director Jon Watts to kick things off, Morgan more or less kicked the can over, going back to his prosecutor roots and explaining the

difference between criminal fraud and commercial fraud.

"At the least," Morgan explained, "it’s causing or inducing someone to take action and not action based on a set of

information that you either know or have a reason to believe might not be true. Or did not take appropriate care to ensure that it was true."

advertisement

advertisement

In case that explanation of commercial fraud

wasn't absolutely clear, Morgan added: "Willful ignorance can absolutely be fraud. That's really important, because of lot of people don't want to know. And not wanting to know, but transacting --

knowing that you don’t know and are not inspecting, when you have a duty for inspection – that’s fraud."

While the other panelists didn't necessarily agree with Morgan's

stringent definition, they concurred that it falls along a spectrum from blatant criminal actions to negligence to willful ignorance, but whatever the state of the mind of industry practitioners, they

are all somehow culpable for something in the order of at least $1 billion and as much as $7 billion in fraudulent CTV ad impressions.

Kudos to Morgan for putting the industry's feet to the

fire on this one. Not just because of the magnitude of the ad dollars involved, but because of the "downstream" effects it has on the marketplace -- and arguably -- society overall.

“You

have to understand the consequences of all the secondary and tertiary effects," he explained, adding: "And so, the question is, what’s happening because you are taking money away from a premium

publisher by suppressing the pricing?"

Among other things, Morgan said that's money that might otherwise be directed to professional studios and journalists.

“There’s a lot of downstream consequences that are significantly higher, and have a consequential impact than just the straight take rate of this $5 billion to $7 billion," he

explained.

To which CIMM's Watts exclaimed: "It's 2025. Why is it technically, commercially, operationally feasible to have a market in which there are billions of dollars of fraud?"

Morgan's answer: "The number of people that make money on every impression that’s delivered, irrespective of it is provably fraudulent, massively outweighs the number of people that

care and will expose something.

"Everybody benefits," he explained, suggesting that it goes all the way to the top, including clients who simply turn a blind eye in order to get cheap,

high-volume CPMs.

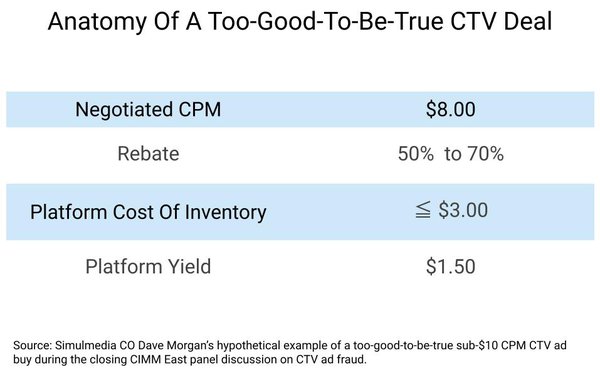

Morgan even provided some math on that (see above), providing a hypothetical example of what the actual yield of a cheap CTV CPM might be, after agency/client rebates. Now a

$1.50 CPM may not seem like much, but $1.50 here and $1.50 there and pretty soon you're talking about some real money. Like several billion dollars real.

"If we see volumes like that, that

actually means someone yielded out $1.50, that can’t be real," Morgan emphasized, citing that is just the sort of thing that happened during the 2024 election cycle, especially for

"locally-based geo inventory on platforms at the highest demand that there has ever been for CTV a particular type.

"It was pure synthetic delivery. And it was moved by significant players in

the industry."

By "synthetic," Morgan means it was completely bogus.

While Morgan may have been the most impolitic of the panelists, he was not alone in the belief that it's not just

sellers of bogus CTV ad impressions that are committing commercial fraud, but some of its buyers too.

"Who exactly are we appealing to to be responsible?" Check My Ads Institute COO and former

Chief Privacy & Responsibility Officer at Interpublic's UM unit Arielle Garcia asked rhetorically, noting: "This is now baked into the commercial model of holding companies, as well."

You don't need to be a forensics accountant to understand where the blame is for the lax oversight enabling the magnitude of commercial fraud within the CTV -- or for that matter, many other

fraudulent ad marketplaces -- because as the CIMM East panel concluded, there are motives up and down the food chain.

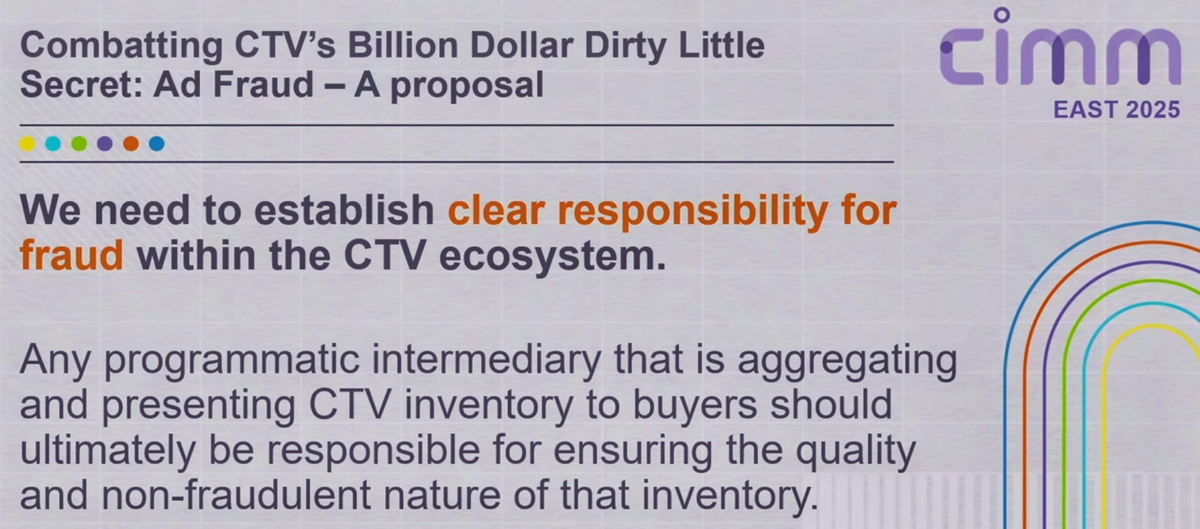

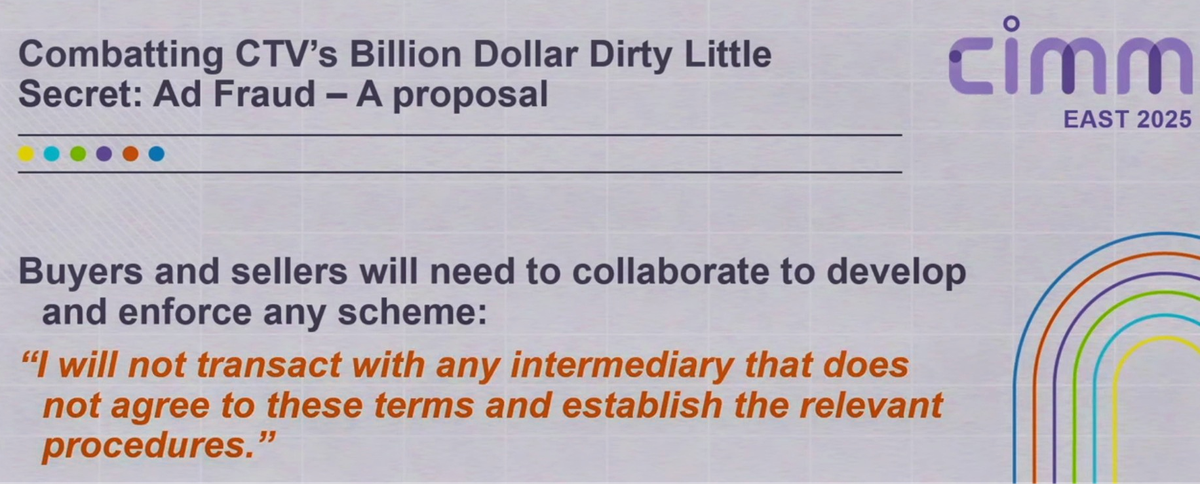

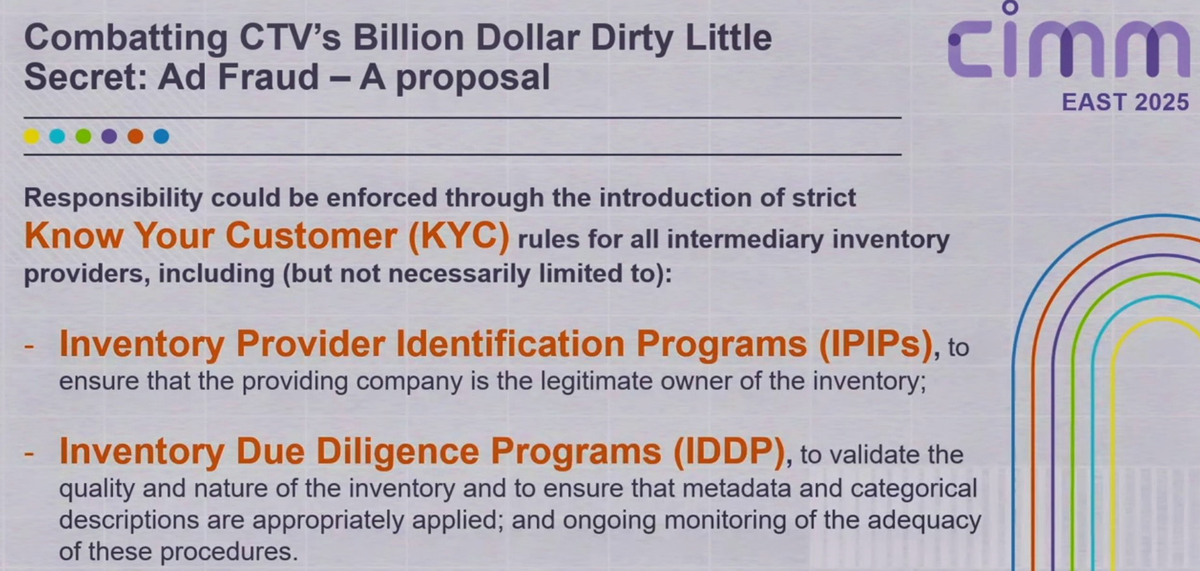

The panelists did have some worthwhile suggestions for how to fix it,

including the use of "filters" to weed out fraudulent deals before they happen, as opposed to using reports to detect them after they happen.

And the session even showed some suggestions from

a CIMM working group trying to tackle the problem (see slides below).

But the bottom line seemed to be more about the most common sense cure for fraud in any industry: knowing and working with

trusted partners who aren't the kind that are bound to screw you -- or even let you screw yourself.

"Our industry relies on trust," Morgan noted, suggesting that as hard as it might be to call

others out for fraudulent behavior, it's something the ad industry needs to do more of.

As someone who has covered the business for more than 40 years, I can tell you first-hand that is hard

to do, and in my years, I've been surprised how many times I've covered stories about the most blue-chip organizations -- J. Walter Thompson (Marie Luisi syndication scandal), Ogilvy & Mather, etc. -- committing various acts of fraud, sometimes willfully.

And I also take exception

that this is some kind of new behavior related to the opportunism associated with digital media, including CTV.

Analog media-buying has always had ad fraud too, and while much of it was errors

or breakage (discrepancy resolutions, etc.), a lot of it was explicitly fraudulent too.

Kudos to CIMM for shining more light on it though, because the complexity -- not to mention the multiple

"hops" -- in the programmatic digital supply chain surely great more opportunities for it.

And if anyone wants to shed even more light on it, MediaPost would be happy to cover it. Heck, I'll

even buy lunch.