Commentary

How We Went From Magic Cookies To The Art Of Misdirection

- by Joe Mandese @mp_joemandese, March 18, 2021

When the first digital identity

trackers were conceived in the nascent days of the web in the early 1990s, they were originally coined "magic cookies."

The term came from a concept already utilized by computer programmers, but early web developers lent the name to HTTP cookies, because they envisioned these new identity trackers would enable all sorts of content and commerce to be delivered and exchanged over the internet.

They were right. But fast-forward to the privacy-savvy 2020s, and the term magic takes on an entirely new connotation: the art of misdirection.

While many consumers have some implicit knowledge why digital identity trackers exist, most don't understand what the explicit value exchange is with publishers and marketers.

As a result, watch as the majority of them perform a disappearing act as soon as they can.

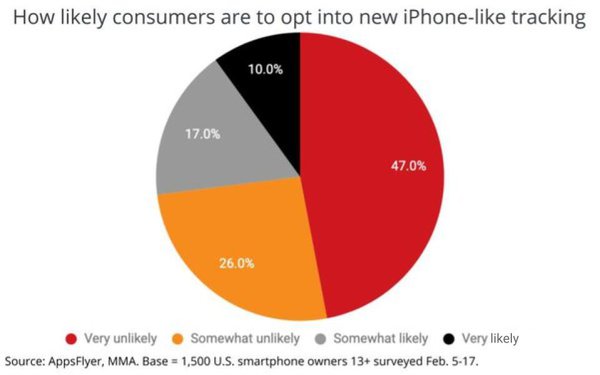

According to a new study released this week by apps attribution analysts AppsFlyer and the Mobile Marketing Association, three-quarters of American smartphone users are likely to opt out of having their identity tracked as soon as they receive an IDFA notice like the one Apple is about to introduce.

What's remarkable to me is that 27% are likely to opt into continuing to have their identity tracked, which underscores the dichotomy of knowledge about the implicit value exchange between digital media and the people who consume it.

Not surprisingly, the study also finds that younger consumers are more likely to accept identity trackers, which either indicates they are more knowledgeable -- or that they are just culturally attuned to being tracked.

The study also indicates that slight majorities of consumers understand that apps use their identity for two purposes: to target them with ads and/or to improve their user experiences, but without an explicit understanding of which apps do so and when -- and perhaps most importantly, how individual users benefit explicitly from sharing their identity.

Instead, the whole process is likely to feel like, well, smoke and mirrors.