Musk's X Corp. Sues Minnesota Over Deep Fake Law

- by Wendy Davis @wendyndavis, April 24, 2025

A "vague and unintelligible" Minnesota law criminalizing “deep fakes” violates the First Amendment, Elon Musk's X Corp. alleges in a lawsuit filed this week.

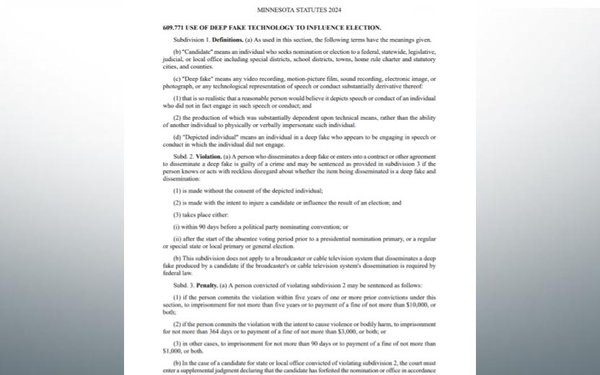

The law, passed in 2023 and amended last year, makes it a crime to share a “deep fake” within 90 days of an election or primary convention, if whoever shared the material knew it was a "deep fake" and intended to harm a candidate's reputation or influence the election.

That statute is “so vague and unintelligible that social media platforms cannot understand what the statute permits and what it prohibits, which will lead to blanket censorship, including of fully protected, core political speech,” X alleges in a complaint filed Wednesday in U.S. District Court in Minnesota.

advertisement

advertisement

The company is seeking a judicial declaration that the law is unconstitutional, and an injunction blocking enforcement.

The measure provides for criminal penalties, including fines, and allows for enforcement by the Minnesota Attorney General, county attorneys, city attorneys, the person depicted in the “deep fake,” and a candidate for office who “is injured or likely to be injured" by the images.

X argues that law violates the First Amendment for numerous reasons, including that it “has the effect of impermissibly replacing the judgments of social media platforms about what content may appear on their platforms with the judgments of the state.”

The company also says the enforcement system, including possible criminal penalties, “provides enormous incentives for social media platforms, such as X, to censor speech on their platforms that the government disfavors -- here, content that constitutes a “deep fake” under the statute.”

“Platforms may be prosecuted criminally or can be sued if governmental officials, depicted individuals, or candidates think the platform has not censored enough content; but the platform may not be prosecuted or sued by anyone if it has arguably censored too much content under the statute,” X adds. “The result is a system that highly incentivizes platforms to remove any content that presents a close call to avoid criminal penalties and costly lawsuits altogether.”

X asserts in the complaint that the law contradicts a history of strong First Amendment protections for speech that criticizes politicians -- including speech that might be false -- as well as a history “of skepticism of any governmental attempts to regulate such content, no matter how well-intentioned they may be.

The Minnesota statute “runs counter to these principles by attempting to impose by 'authoritative selection' the permissible content on social media platforms, rather than allowing the 'multitude of tongues' engaging in political debate and commentary on those platforms to do so,” X argues.

The company adds that the law is unnecessary because X has other safeguards against deep fakes -- including “Community Notes,” which allows users to alert others that images on the platform may not be authentic.

Musk isn't the only one suing over the statute. Last year, social media influencer Christopher Kohls and state lawmaker Mary Franson also sought an injunction blocking enforcement on First Amendment grounds.

In January, U.S. District Court Judge Laura Provinzino rejected their request for an injunction.

She ruled that Kohls lacked “standing” because his content was labeled as parody and therefore wouldn't deceive anyone, and that Franson waited too long after the law took effect to seek an injunction.

“Representative Franson’s failure to act with the requisite diligence does not justify the 'strong medicine' of facial invalidation at this juncture,” Provinzino wrote.

Kohls and Franson appealed that ruling to the 8th Circuit, arguing in a brief filed Wednesday that the law “flagrantly violates the First Amendment,” and “is a content- and viewpoint-based restriction on core political expression.”

“The law criminalizes parody, satire, and core political criticism -- speech at the heart of the First Amendment,” they argue. “Its vague and subjective terms, (e.g., whether a video is 'realistic' to a 'reasonable person') invite discriminatory enforcement,” they argue. “The statute discriminates on the basis of viewpoint by prohibiting content intended to 'injure' a candidate while allowing laudatory depictions, and by exempting candidate-approved speech.”

X Corp. and others have separately sued over California legislation that would regulate election-related deep fakes.