Facebook says marketers that are suing the company for

allegedly overestimating the potential reach of ad campaigns shouldn't be able to proceed with a class-action lawsuit.

In papers filed late last week, Facebook argues that the claims don't

lend themselves to class-action treatment, in part because advertisers on Facebook don't have enough in common with each other.

“Each ad an advertiser purchases is a different product

with a different price based on different information and performance objectives,” Facebook writes in a motion filed with U.S. District Court Judge James Donato in the Northern District of

California.

If Facebook prevails with this argument, advertisers could still sue the company individually. But doing so could be prohibitively expensive for some small advertisers.

The

company's argument comes in a dispute that dates to August of 2018, when Facebook was sued for allegedly inducing advertisers to purchase more ads -- and pay higher prices for them -- by inflating the

number of users the ads could reach.

advertisement

advertisement

The current plaintiffs are the Colorado-based e-commerce store operator DZ Reserve, and Max Martialis, which sells weapons accessories.

The initial

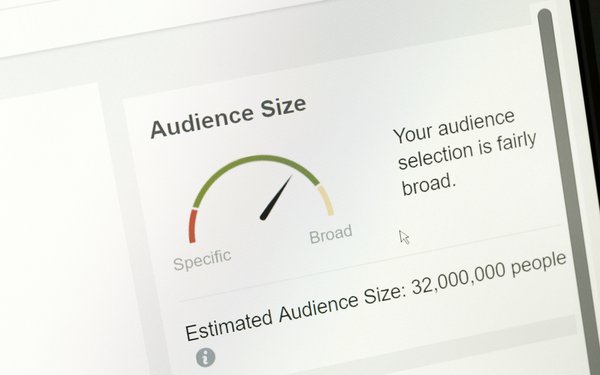

complaint against Facebook drew on reports by outside groups, including the industry organization Video Advertising Bureau, which said in 2017 that Facebook's estimates of audience reach in every

U.S. state were higher than the states' populations.

The advertisers added in an amended complaint filed last year that Facebook employees were aware of complaints about the potential reach

metric since September of 2015, but failed to respond appropriately.

Last month, the advertisers officially asked Donato to certify the lawsuit as a class-action. They broadly sought to

represent U.S. residents who purchased at least one ad since August 14, 2014 from Facebook or Instagram through Facebook's Ad Manager or Power Editor. (The proposed class definition contained several

exclusions -- including for ads that aimed to persuade people to take an action, such as liking a page, and for ads with a potential reach estimate lower than 1,000, among others.)

“Facebook's fraudulent course of conduct is a common question because it is susceptible to proof through common evidence,” the advertisers argued in their request for class

certification. “Facebook deceived -- and continues to deceive -- its advertisers by providing an inflated potential reach. In addition, the potential reach metric is false and misleading because

it is not based on unique people.”

Facebook previously said in court papers that estimates about campaigns' reach are not guarantees, and that they don't affect billing.

The

company argues in its newest papers that DZ Reserve, and Max Martialis “fail to present evidence showing that advertisers as a class uniformly relied on 'inflated' potential reach estimates to

increase their budgets.”

Facebook also says members of proposed class don't use the potential-reach metric as a tool for setting budgets.

Potential reach is a planning tool that

some advertisers use to help create a target audience for their ad campaigns -- not for setting budgets,” Facebook writes.

The company adds that it discloses that potential reach is not

an estimate of how many people will see an ad, writing that it provides estimates of actual results -- including estimated daily reach -- which is "a fraction of" the potential reach estimate.

Facebook additionally argues that the dispute doesn't involve the kind of alleged “uniform” misstatement or omission that lends itself to a class-action lawsuit.

“This

case does not involve a single product with a single misstatement on an identical label sold at the same price,” Facebook writes. “Rather, advertisers bought ads with individualized

potential reach estimates that reflected different targeting criteria; selected different objectives for their campaigns and measured performance based on different information (not including

potential reach); and bought at different times and at different prices.”

Donato is slated to address class certification at a hearing on June 10.